April 15, 2021

Industry, agencies continue preparing for African swine fever

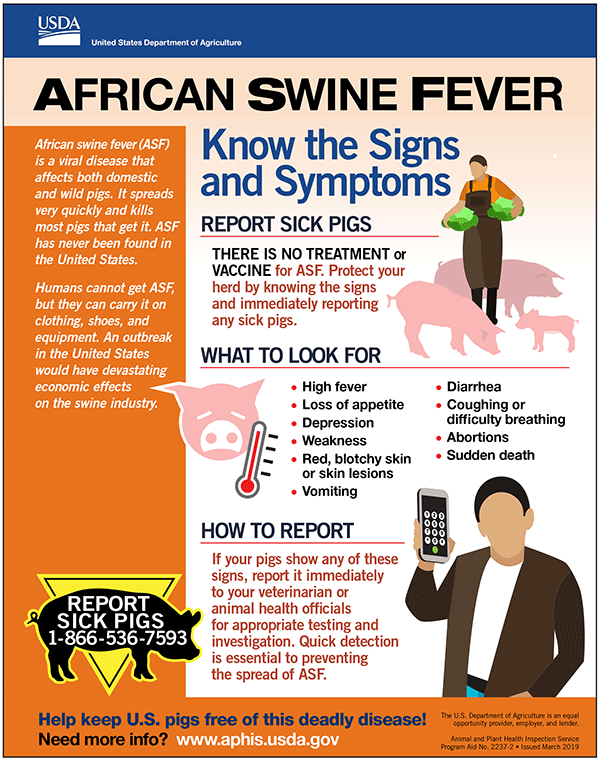

African swine fever outbreaks are killing pigs in at least 26 countries, and U.S. veterinarians worry about the potential for incursion into their clients’ barns.

In March, veterinarians at the American Association of Swine Veterinarians annual meeting (see story) said swine veterinarians and pork industries continue planning how to keep the virus from reaching the U.S. through trade, as well as how to continue raising pigs and selling pork if it does.

ASF kills about 90% of infected pigs. Since 2007, it has spread through the Caucasus region, the country of Georgia, and into Europe. In 2018, it emerged in China, which is the world’s largest pork producer and a supplier of feed ingredients for U.S. pigs.

The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) reported that, as of mid-February, ASF outbreaks were occurring in 12 countries in Asia, nine in Europe, and five in Africa. OIE officials also published guidelines in February on compartmentalization within countries, or establishing populations of swine free of the disease and eligible for trade while the national government works toward full eradication.

Dr. Wesley Lyons, a veterinarian with Minnesota-based Pipestone Veterinary Services, has worked with swine producers in China to protect pigs from ASF. He described added measures to keep the virus out or inactivate it, such as cooking incoming feed, banning pork products from employee lunches, and using showers at control points.

He also noted prior research that indicates ASF could survive ocean crossings to the U.S. in feed ingredients.

“Our hope, our goal, our wish is for a responsible imports plan that is federally mandated,” he said. “Obviously, we want to develop a science-based plan to safely import essential ingredients from countries of high risk.”

Dr. Keith Erlandson, senior technical service veterinarian for Zoetis, also worked in China and described measures such as multiple washings and heat treatments for trucks between deliveries, holding times for supplies arriving on farms, whole-herd testing, and environmental swabbing.

He described living with ASF as entering a new era of biosecurity, requiring more time and labor to reduce losses.

Dr. Tiffany Lee, director of regulatory and scientific affairs for the North American Meat Institute, said industry groups are working with government agencies to prepare. Among industry’s concerns, she said, pork producers want consistent plans among states, see gaps in plans for depopulation and disposal, expect a need to reassure the public that pork remains safe during an ASF outbreak, and will continue working on plans to keep slaughter plants running during an outbreak.

Last year, the OIE and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations published a five-year plan toward global control of ASF, calling on governments to make long-term commitments to tackle it as a global threat.

“Despite this daunting and complex challenge, the global control of ASF is feasible, but unlikely to be successful and sustainable without determined national efforts,” the document states.

The document also calls for coordinated vaccine research and development, as well as studies on subjects such as ASF in wild pigs and the role of ticks in spreading the disease.

Dr. Jack A. Shere, associate administrator at the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, said during the AASV meeting that ASF threatens an industry that produces 20 billion pounds of meat and supports more than 500,000 jobs.

“For economic, food security, and animal health as well as welfare reasons—which are compounded by the lack of a commercially available vaccine—we take ASF and the threat of ASF extremely seriously,” Dr. Shere said.

Controlling the disease requires collaboration on issues of surveillance, depopulation, and disposal.

APHIS officials work with U.S. Customs and Border Protection personnel, for example, to evaluate swine, pork, and germplasm among other products that could carry ASF, he said. Animal disease laboratory groups have been coordinating research on methods to detect the disease and prevent its spread.

And APHIS officials have been in talks with partners in Mexico and Canada on ASF prevention and mitigation, as well as planning a forum for discussions with South American countries.

“The pandemic has emphasized the importance of preparedness and coordination for all high-consequence livestock diseases as well as the need for advance planning,” Dr. Shere said. “We’re thankful for the domestic and international partnerships that we have.”

On March 16, USDA officials announced an agreement with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency that, while the countries would halt trade in swine and swine products following ASF detection in one of the countries, they would follow an agreed protocol to reduce restrictions on shipping swine, swine germplasm, and other swine-source products. The protocols involve the affected country taking actions such as establishing control areas, conducting surveillance, and removing feral swine.

Researchers developing ASF vaccine candidates

The world lacks effective, approved vaccines against African swine fever, a devastating disease that can wipe out herds.

U.S. scientists are among those trying to create vaccines that could reduce swine deaths and prevent further spread of the disease. ASF has been devastating in China, killing upward of hundreds of millions of pigs, and U.S. veterinarians at the recent annual meeting of the American Association of Swine Veterinarians described the impact of the disease on daily operations and the preparations in the U.S. to prevent or control outbreaks.

U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service officials announced in January that scientists at Plum Island Animal Disease Center had made progress on four vaccine candidates developed through gene deletions that weaken the virus. The agency licensed the vaccine candidates to companies for further development.

During last year’s AASV annual meeting, a veterinarian who had worked in China said unapproved vaccines available to farms at the time could save half a herd.

Reuters reported Jan. 21 that two ASF strains circulating in China lacked one or two of the same genes that had been deleted to produce a vaccine candidate currently in trials, and the new strains circulating on farms may have developed from unapproved vaccines created by people who replicated the viral sequences for the vaccine candidate. The new strains are less deadly, but they cause chronic illness and farms cull the pigs anyway, the article states.

Information from the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) indicates keeping ASF out of a country depends on importation policies and biosecurity measures that keep out infected pigs and contaminated pork products. Control during an outbreak can be difficult, and experiences in Europe and Asia show transmission can depend, in part, on the density of wild boar populations and their interactions with low-biosecurity pig production systems. Soft ticks also may present risks.