August 01, 2021

Rabbit, hare populations recovering from viral disease

Rabbit and hare populations in the Western U.S. seem to have rebounded quickly after outbreaks of a deadly viral disease.

Dr. Julianna B. Lenoch, national wildlife disease program coordinator for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service’s Wildlife Services, said lagomorphs that either survived infections with rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus serotype 2 or avoided infection were quick to reproduce following dips in local populations. As a result, wildlife managers reported they found no signs of broader impacts on food webs, including those involving predator species.

Animal health authorities first found RHDV2 among U.S. wildlife in March 2020, when laboratory testing identified the virus in rabbits and hares found dead in New Mexico.

The virus had been identified since February 2018 among pets and feral European rabbits in British Columbia, Ohio, Washington state, and New York City, but its impact had been limited before it emerged in the Southwest.

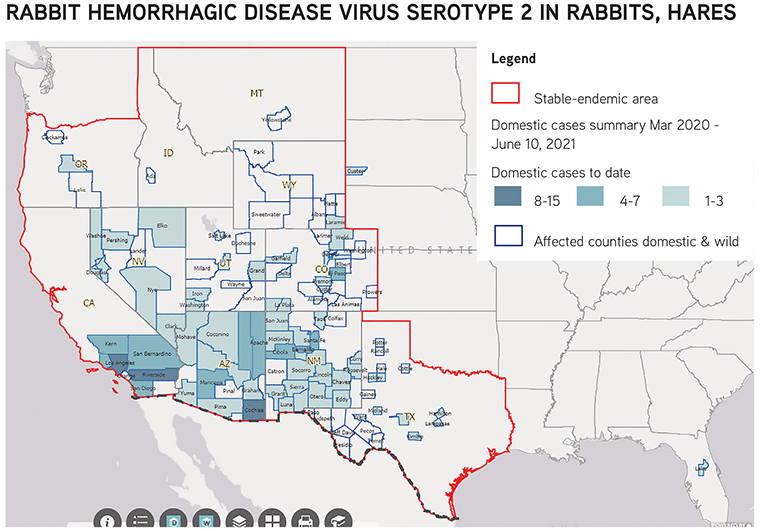

Since then, RHDV2 has spread to a mix of domestic and wild rabbits and hares in at least 11 states and northern Mexico, causing die-offs among naive populations. The affected animals include species native to North America and European rabbits that live either in captivity or as feral populations.

APHIS officials have previously reported that evidence from die-offs suggested the virus has a mortality rate somewhere between 50% and 90%.

Rabbits and hares infected with RHDV2 often die without clinical signs, sometimes with blood-tinged nostrils, APHIS information states. Clinical signs in affected animals can include neurologic signs, respiratory disease, and jaundice, and survivors may show dullness and anorexia. The virus causes disease in rabbits as young as 15 days old.

Dr. Peter Mundschenk, Arizona state veterinarian, said it’s unclear how long RHDV2 will circulate in wild rabbits, but it is now considered at least nearly endemic in the Southwest. Confirmed infections have occurred throughout his state since spring 2020.

“A year ago, we were having reports in our really heavily hit areas of dead rabbits everywhere,” he said.

But his office is receiving fewer reports of deaths from the virus this year, and he hopes that is a sign the infection rate is decreasing.

Dr. Ralph Zimmerman, New Mexico state veterinarian, said he received a few reports in late spring of deaths among wild cottontails. But populations in his state, too, had largely recovered from lows in 2020.

“Most of the places where we saw very few or no rabbits last year, as far as wildlife, we’re seeing rabbits back again this year,” he said.

Stalled at the Plains

From 2016 through early 2020, animal health authorities discovered sporadic cases of RHDV2 infections among domestic rabbits and feral European rabbits in Quebec, British Columbia, Washington state, Ohio, and New York City. One isolated infection occurred in Florida near the start of 2021. All other recent confirmed infections have occurred in the West.

Bryan Richards, emerging disease coordinator for the U.S. Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center, said it’s unclear why all of the recent RHDV2 infections occurred to the west of a line running from Mexico City to southern Montana. He cited a USGS map that shows confirmed infections throughout the range of jackrabbits and desert and mountain cottontails but halting at the Great Plains.

“Why are we not picking up disease moving east?” he said. “After all, when you get into this area, you’re starting to get into eastern cottontail country—fairly contiguous habitat, one would suggest—and so it’s kind of an anomaly.”

APHIS reports confirm at least some eastern cottontails have become infected in the wild, along with desert and mountain cottontails as well as antelope and black-tailed jackrabbits and brush rabbits. APHIS research also has shown eastern cottontails are susceptible to experimental infection with RHDV2.

APHIS officials are working with local wildlife managers to protect endangered and threatened species in North America and collections in zoos. Officials from the Oakland Zoo announced in September 2020 they had been working with state and federal wildlife partners to capture endangered riparian brush rabbits and vaccinate them against RHDV2 to protect them from extinction.

Dr. Julia Lankton, wildlife pathologist for the USGS National Wildlife Health Center, said the virus may be more lethal to certain lagomorph species, but that difference is hard to see without more information.

“The mortality rate is really difficult to know when you don’t know how many are infected, how many survived, and how many died,” Dr. Lankton said.

Richards said state wildlife agencies conduct population surveys for deer, ducks, and other game species, but few do so for rabbits. USGS is offering states guidance on methods of surveying rabbit populations.

While Richards said it also would be interesting to trap wild rabbits after an outbreak and test whether they have immune responses to the virus, he’s unaware of any state agencies conducting such testing.

Protecting domestic, endangered animals

Some cases of the disease have been detected in eastern Wyoming, not far from the Nebraska border. Todd Nordeen, disease and research program manager for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, said his agency is conducting field surveillance of wild rabbit populations, investigating reports of rabbit deaths, and educating the public on the disease. His office also is coordinating with the Nebraska and U.S. agriculture departments and would follow their protocols in responding to potential RHDV2 infections.

Given the infections in neighboring states, Nordeen said, “It is likely just a matter of time before it is confirmed in Nebraska.”

Dr. Dennis A. Hughes, Nebraska state veterinarian, said his office has been warning rabbit exhibitors about the virus and the need for biosecurity.

RHDV2 spreads through contact with an infected rabbit’s waste or blood, as well as through contaminated food or water, APHIS information states. People can carry viable virus into a rabbit pen on their clothing or shoes. The virus also remains viable through extreme temperatures.

Dr. Lenoch encourages rabbit owners to reinforce their biosecurity at home and take extra care in transporting their rabbits. Veterinarians who see unexplained deaths or suspected infections should contact state animal health authorities.

“It’s a scary disease and one that should be respected,” Dr. Lenoch said. “We want our pet owners to certainly be vigilant, cautious, and careful if they’re anywhere where the virus is known to be.”

APHIS officials are allowing use, under special permits, of two killed RHDV2 vaccines licensed in the European Union. No RHDV2 vaccines are licensed in the U.S.

Dr. Mundschenk, of Arizona, said local veterinarians have been administering the European vaccines to owned rabbits in his state. He noted that the death rates in naive herds had varied widely, wiping out some herds yet killing only fragments of others.

Dr. Lenoch also noted RHDV2’s arrival in the U.S. is part of an unexplained global trend. Animal health authorities on other continents also began dealing with the arrival of RHDV2 in 2020 and 2021, with outbreaks occurring in China, Iceland, Israel, Japan, Nigeria, Norway, Senegal, Singapore, and the United Kingdom.

“We are working with our global partners on that, to share genome sequences to see if they’re closely related and see if we can figure out whether there’s any other routes of exposure for disease transmission,” she said.