April 15, 2020

Can veterinarians prevent the next pandemic?

The COVID-19 pandemic marks the third novel coronavirus outbreak of the 21st century.

Unlike the viruses that cause severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome, which were associated with outbreaks limited in scope, SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19—burned across the globe in just over two months since the first case was reported last December in Wuhan, China.

Most countries, including the United States, were soon scrambling to manage the public health crisis.

On March 11, the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic. At the time, the WHO stated that more than 118,000 human cases of coronavirus disease had been reported in 114 countries, along with nearly 4,300 human deaths.

“We are deeply concerned by both the alarming levels of spread and severity, and by the alarming levels of inaction,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom said.

“We have never before seen a pandemic sparked by a coronavirus.”

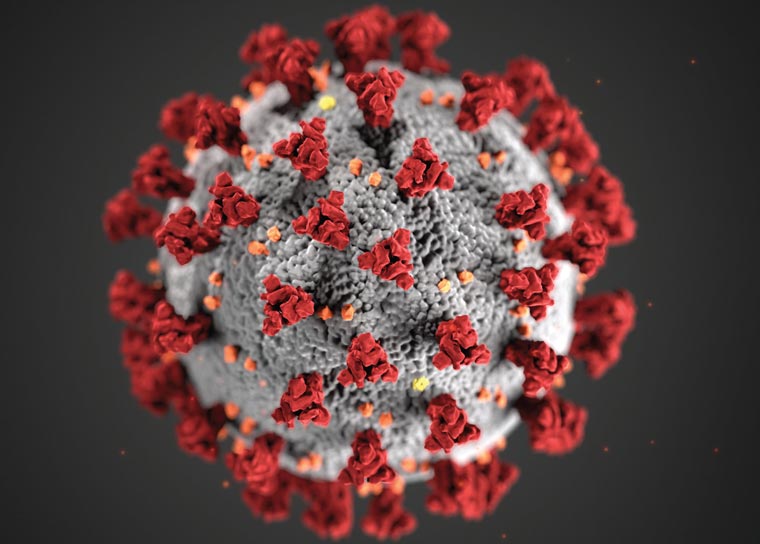

Coronaviruses

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses that have been found in dogs, cats, horses, cattle, swine, chickens, turkeys, humans, and bats. Several bat coronaviruses have been shown to be zoonotic pathogens, and the human illnesses they cause range in severity from a mild cold to severe pneumonia, with the potential to be fatal.

“It’s important to recognize that there are a number of coronaviruses that have infected people for decades. These viruses often represent 10 to 20% of all the common colds in people,” said Dr. Christopher W. Olsen, professor emeritus of public health at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine and School of Medicine and Public Health.

For unknown reasons, neither SARS nor MERS were as highly infectious and adapted to human-to-human transmission as the COVID-19 virus.

Linda Saif, PhD, professor and coronavirus researcher, The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine

Dr. Olsen spent much of his career studying zoonotic infections and was a consultant to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention during the SARS epidemic. Coronaviruses in general aren’t becoming more lethal to humans, Dr. Olsen explained. Rather, the viruses that cause SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 are each novel coronaviruses that humans have no immunity against and are fully susceptible to.

While the SARS and MERS viruses are more lethal than the COVID-19 virus, neither are as infectious as this latest novel coronavirus, according to Linda Saif, PhD, a professor and coronavirus researcher at The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine.

The case fatality rates for SARS and MERS have been 10% and 34%, respectively, Dr. Saif explained. The estimated fatality rate for COVID-19 ranges from less than 1% to as high as 3.4%. “For unknown reasons, neither SARS nor MERS were as highly infectious and adapted to human-to-human transmission as the COVID-19 virus,” she said.

“As RNA viruses, with their ability to recombine and acquire mutations, coronaviruses are more likely to evolve and gain the ability for interspecies transmission, similar to influenza viruses,” Dr. Saif continued. “This is partly why we are seeing coronaviruses more frequently causing these pandemics.”

A likely explanation for the origin of the COVID-19 virus is that it is a recombinant coronavirus generated in nature from a bat coronavirus and another coronavirus in an intermediate animal host, Dr. Saif explained. Initially, pangolins were thought to be that host, but viral sequencing indicated that likely isn’t the case, she said.

Viral hosts

Bats are as diverse as the viruses they carry.

With more than 1,300 bat species found throughout the world, bats are the second-largest order of mammals after rodents.

Researchers have studied bat behavior, feeding habits, migratory patterns, and echolocation. Yet few early studies looked at bats as hosts of viruses beyond the rabies virus.

That changed with the 2003 SARS epidemic, which was ultimately linked to bats. Since then, more than 120 viruses have been identified in various bat species, including several novel coronaviruses, as well as the Ebola, Hendra, and Nipah viruses.

Today, bats are increasingly considered one of the most important animal reservoirs for emerging infectious viruses.

The ways a bat might have directly infected a human with COVID-19 include a human eating the bat, in soup, for example, or coming into contact with bat feces or secretions at the exotic animal markets common in China, Dr. Saif said. Likewise, bat feces are sometimes sold in stores for use in Chinese traditional medicine, she said, adding that fruit or other foods contaminated with bat feces or urine might be a foodborne route of transmission to humans.

Deja vu all over again

Veterinary epidemiologist Dr. Donald Noah isn’t surprised that a novel zoonotic virus is responsible for the current pandemic.

“Something like this was going to happen, and it will happen again,” said Dr. Noah, an associate professor of public health and epidemiology at Lincoln Memorial University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Prior to his academic career, Dr. Noah held senior leadership positions with the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, where he served as deputy assistant secretary for biodefense against weapons of mass destruction. As acting deputy assistant secretary of defense, Dr. Noah was part of the government response to the 2009-10 pandemic of swine flu, or H1N1 influenza, that killed some 12,000 Americans.

“Even when the COVID-19 pandemic is over, we’re not going to be able to wash our hands of this, literally or figuratively,” Dr. Noah said. The ongoing expansion of human populations into wildlife habits, he explained, means more frequent human-animal interactions that make exposure to a new zoonotic disease more likely.

Dr. Noah is hesitant to use the phrase “silver lining” about an ongoing pandemic, but he hopes Congress will be compelled to be proactive about preventing these public health crises before they begin by enacting one-health legislation.

“Zoonotic pathogens don’t perceive species differences. They don’t perceive geographic boundaries,” he said. “The problem is disease surveillance and response systems are siloed between the human, veterinary, and environmental communities.

“Federal agencies have no choice but to merge their efforts against these pathogens. The alternative is to continue to accept unchecked disease emergence.”

“There’s not a lot we can do about disease emergence,” Dr. Noah concluded, “but what we can do is be better prepared to respond quicker, more effectively, and in a more collaborative way that minimizes the loss of life and economic hardships.”

Reverse zoonoses

Dr. Saif said veterinarians should be involved in all aspects of zoonotic infections, in concert with a one-health approach.

“Veterinarians need to be part of identifying the animal reservoirs and the intermediate hosts for these diseases,” she said. “This may focus on wildlife medicine, such as understanding the habitats and diversity of bat species as reservoirs for coronaviruses and multiple other viruses.”

Even when the COVID-19 pandemic is over, we’re not going to be able to wash our hands of this, literally or figuratively.

Dr. Donald Noah, veterinary epidemiologist and former deputy assistant secretary for biodefense against weapons of mass destruction with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security

Additionally, studies of bat physiology and immunity are critical to understand how bats can harbor so many viruses without disease, according to Dr. Saif.

“A similar emphasis is needed for avian species that transmit avian influenza and for swine as influenza hosts,” she explained. “The question of what factors influence interspecies transmission remains unknown.

“Also, more veterinarians should be working with other researchers to develop the most appropriate animal models for these diseases since we cannot test antivirals or vaccines without an animal model that reproduces the human disease and responses.”

Regarding whether a pet can be infected with COVID-19 virus by a sick owner, Dr. Saif noted that researchers will want to investigate that. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has indicated that there is no evidence that pets become sick and that there is also no evidence to suggest that pet dogs or cats can be a source of infection with SARS-CoV-2, including spreading COVID-19 to people. The AVMA has developed a series of FAQs that includes this topic.

“Veterinarians should be at the forefront of this research to investigate if a new disease can cause a reverse zoonosis and transmit from humans to pets and livestock,” she said.