April 01, 2020

CWD spreading, sometimes long before discovery

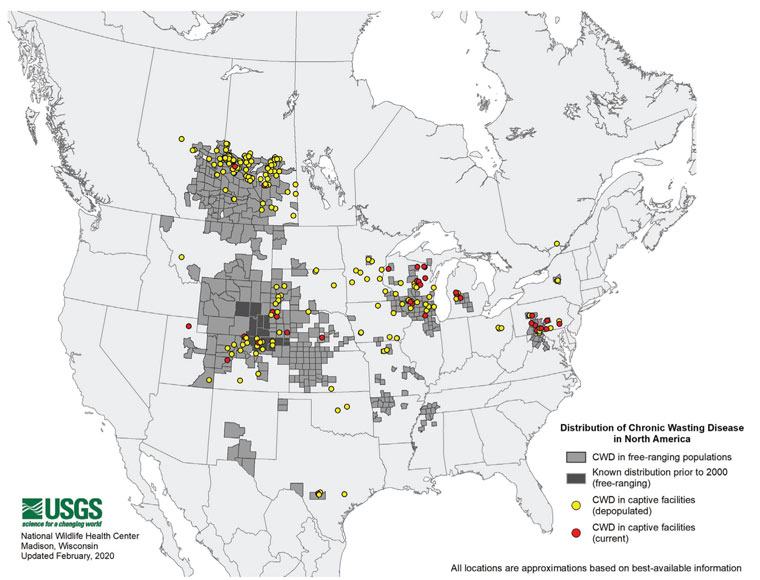

Animal health authorities are finding chronic wasting disease in more counties each year.

About four in 10 wild cervids are infected with CWD in areas of Colorado, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. The always-fatal prion disease also can simmer undetected in remote clusters of animals, as apparently happened in Arkansas and Tennessee along the states’ shared border.

Bryan Richards, emerging disease coordinator for the U.S. Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center, said CWD’s known footprint has grown substantially over the past 10 years. Until a few years ago, he felt confident surveillance also would identify any areas where CWD had become endemic.

Arkansas Game and Fish Commission information indicates the agency learned in February 2016 that the disease was in Newton County, which includes areas in and along the Ozark Mountains.

“Later testing determined that the disease has likely been in the state for decades before being detected,” commission information states.

Initial sampling found a disease prevalence of 23%.

Dr. Jennifer R. Ballard, Arkansas state wildlife veterinarian, said the infected deer lived in an isolated area where state authorities have difficulties observing animals. She also noted that, because CWD infections tend to occur in clusters, historical surveillance models may have underestimated the number of animals that needed to be tested to be confident an area was free of the disease, although she said newer models are based on better information.

How the disease arrived in the state is unknown.

Laboratory tests have now confirmed infections in 26 states and three Canadian provinces. Montana authorities first found CWD in the state in 2017, south of Billings, and the state now has infections in at least three regions.

Montana authorities reported finding 142 animals with confirmed CWD infections during the 2019 hunting season, April 2019 through January 2020. Those animals were 86 white-tailed deer, 53 mule deer, two moose, and one elk.

Control efforts, results vary

Reindeer in Norway developed CWD in 2016, and Richards said tremendous surveillance suggested the disease was new to the country and environmental contamination should be low. Local authorities depopulated the affected herd through hunters and government sharpshooters and plan to leave the area free of reindeer for five years. He expects the disease elimination effort will succeed.

In North America, some state and provincial authorities have canceled efforts to control deer populations amid opposition from constituents. Wisconsin and Alberta responded to initial outbreaks with aggressive culling until political opposition halted those efforts.

In southern Wisconsin, state authorities now find CWD in about half of adult male deer killed by hunters and 30% of adult female deer, Richards said. At high enough prevalence, deaths from the disease could tip stable populations into decline.

He cited efforts by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources as an example of partial success. The department expanded hunting in areas with CWD, complemented with state government sharpshooters who focus their efforts in areas known to have the disease.

Disease prevalence remains low in Illinois 15 years after the discovery of CWD in the state, Richards said. The disease expanded into new areas during that time, but he thinks that reflects the limitations of state resources rather than the effectiveness of the methods.

Arkansas authorities increased bag limits and removed antler point–based restrictions on hunting, as well as increased restrictions on feeding and baiting that can bring animals together and increase the risk of disease spread, Dr. Ballard said. State authorities focus on removing bucks and keep a young deer herd, she said.

Richards said facilities with captive cervids and lax biosecurity can spread CWD to wild herds. Facilities of concern include breeding facilities, farms that raise cervids for meat, and caged hunting grounds.

Some researchers are trying to find ways to more quickly detect outbreaks. Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, for example, will receive $800,000 in state funding to investigate whether detection dogs can identify CWD in deer feces as well as look into the potential to create live-animal tests for the prion, according to a February announcement from state authorities.

Host range varies by strain

Debbie McKenzie, PhD, associate professor in the University of Alberta Department of Biological Sciences and Centre for Prions and Protein Folding Disease, said prions can take on different shapes as they enter new animal species. In compatible species, a CWD strain may transmit as is, or the prions may fold the new host’s healthy proteins in new ways, one of which might generate disease and a new strain with a different host range.

“The problem that we have, at one level, is that, until we have a positive in another species, we don’t have a positive control for the diagnostic testing,” Dr. McKenzie said.

Dr. McKenzie’s research involves efforts to develop transgenic mice to test for CWD susceptibility among species such as beaver and pronghorn antelope, which share territory with infected cervids.

“Those are, unfortunately, long-term events because it would be a first passage into a new host,” she said. “So, it quite possibly is going to take 700-plus days for us to get any answer at all.”

In a presentation in December for the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, Dr. McKenzie said experimental evidence showed two CWD strains isolated from deer infected different animals. One infected mice, the other hamsters.

“The big question is always, ‘Does CWD transmit to humans?’” she said. “As of right now, the jury is still out. We have no known cases of human disease linked to CWD. But the thing to keep in mind is that the prevalence of the disease has continued to increase over the last 20 years, so the number of people that have been exposed—potentially exposed—to infected deer has increased.”

She said she expects the risk of human infection to remain low but recommends against eating meat of untested or CWD-positive cervids from areas with the disease. She also indicated CWD likely is a long-term threat where it is prevalent.

Prions bind to soils and remain infective for years to decades, Dr. McKenzie said. They tend to stay within the top few millimeters of clay-containing soils in prairie regions, and deer eat several grams of soil daily.

“Even if we could reduce the deer population in a given area, the CWD present in the soil is going to result in deer in future years becoming infected,” Dr. McKenzie said.