How big is Florida's python problem?

January was a bad month for giant-snake enthusiasts.

First, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the Burmese python, yellow anaconda, and Northern and Southern African pythons as injurious invasive species under the Lacey Act, making it a federal crime to import the non-native snakes or transport them across state lines.

Nearly two weeks later, on Jan. 30, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published the first study documenting the ecologic impacts of feral Burmese pythons in Florida's Everglades National Park. Researchers found evidence suggesting python predation has caused dramatic declines in the numbers of raccoons, opossums, and other mammals in the park.

But, apart from a general recognition that feral pythons and other large constrictors have the potential to upset naive ecosystems, little else about the Sunshine State's invasive snake conundrum isn't in contention.

In dispute are how the giant reptiles first became established in South Florida, the number of Burmese pythons in the region, the scale of non-native snake predation on indigenous wildlife, the chances of pythons and other wild constrictors becoming established elsewhere in the United States, and the impacts of tougher restrictions on the trade and ownership of giant snakes.

Scott Hardin is the exotic wildlife species coordinator for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the state agency responsible for regulating native and non-native species. When it comes to Florida's most problematic invasive species, Hardin says feral pigs top the list. Wild hogs, found throughout the state, are estimated at half a million strong. They damage sensitive wetlands with their rooting, adversely impact agriculture and forestry, and cause erosion on roads, dikes, and levees. They also can be aggressive toward humans and are reservoirs for infectious diseases and parasites.

Burmese pythons are a problem because they prey on native wildlife and threaten already imperiled species, such as the endangered Key Largo woodrat, according to Hardin. In 2010, the commission stopped issuing licenses for people to acquire seven constrictor species as pets, including Burmese pythons. Still, Hardin doesn't think pythons pose a serious danger to people, nor does he believe they can extend their habitat beyond Florida's subtropical climate, as some researchers suggest. For Hardin, it's unrealistic to consider his state's invasive snake population a national emergency.

"There is something about snakes in general, and very large snakes in particular, that just evokes a very visceral reaction amongst people," Hardin observed.

The federal government is taking no chances, however. On Jan. 17, Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar announced four constrictor snake species had joined the mongoose, Java sparrow, and some 200 other exotic animals on the list of injurious wildlife. The injurious wildlife provisions of the Lacey Act authorize the Interior Department to regulate the importation and interstate transport of wildlife species determined to be injurious to humans or the nation's agriculture, horticulture, forestry, or wildlife interests.

Restrictions on the four giant-snake species are warranted, Salazar explained, because they jeopardize the Everglades and other sensitive U.S. ecosystems.

"The Burmese python has already gained a foothold in the Florida Everglades," he warned, "and we must do all we can to battle its spread and to prevent further human contributions of invasive snakes that cause economic and environmental damage."

With its warm temperatures, proximity to Central America and South America, and status as a major international hub, South Florida has long served as a gateway for exotic fish and wildlife coming into the United States, legally or otherwise. In fact, Miami is one of the nation's top ports for reptiles entering the country.

Over the years, so many exotic animals either escaped or were dumped in Florida that approximately 100 species of non-native birds, fish, reptiles, amphibians, mammals, and invertebrates are currently established within the state. Barring a major effort to remove them, wildlife experts expect that these animals are here to stay.

Alarms sound with each discovery of an invasive species, but few are louder than those raised by the Burmese python. Andrew Wyatt, president of the United States Association of Reptile Keepers, believes politics and exaggerated news media reports have overtaken efforts to address the python presence scientifically.

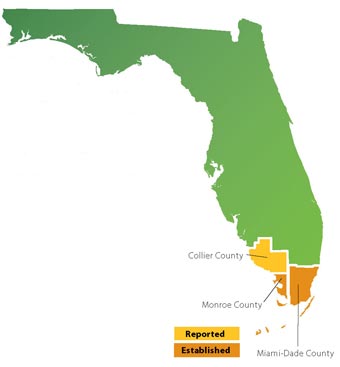

"This is an issue that affects three counties in the state of Florida, not the entire nation," said Wyatt, whose association advocates on behalf of private reptile owners and traders.

The U.S. reptile industry is estimated to have earned revenues of up to $1.4 billion in 2009, according to a 2011 study commissioned by USARK. If all nine constrictor snake species were to be listed as injurious wildlife, the study projected industry losses would range from $76 million to $104 million within the first year, particularly among snake breeders and sellers. Losses over the first 10 years could run between $372 million and $900 million.

Invasive species poster child

Explanations vary as to how a giant constrictor native to southern Asia and Southeast Asia came to make a home in Florida. The state Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission estimates Burmese pythons have inhabited southern portions of the Everglades since at least the 1980s, although reports of loose constrictors date as far back as the 1970s. These snakes may have accidentally escaped, been intentionally released, or both.

One theory popular within the reptile trade but disputed is that Florida's wild python population exploded after hundreds of the snakes escaped from a facility outside Miami that was destroyed by Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

Today, the giant constrictors are established in Miami-Dade and Monroe counties, and possibly Collier County as well. From 2000-2011, a total of 1,825 pythons were removed from within and around Everglades National Park. Estimates on the number of Burmese pythons inhabiting South Florida range from several thousand to as high as 100,000. Additionally, a small colony of boa constrictors has been established in a park outside Miami since the 1970s, and there's evidence suggesting Northern African pythons are reproducing in that region.

That the nation's largest subtropical wilderness is a home to non-native constrictors is understandable. The Everglades comprise 1.5 million acres of mostly isolated saw grass marshes, cypress swamps, pinelands, and mangrove prairies. Burmese pythons have flourished in this environment for several reasons. One of the largest snakes in the world, they can grow as long as 23 feet and weigh up to 200 pounds. They reproduce quickly, with females laying clutches of 100 eggs.

While the American alligator likely remains atop the Everglades food chain, pythons are an apex predator in their own right. They climb trees, ambush prey from land or water, and, according to Dr. Elliott Jacobson, aren't finicky eaters.

"Some snakes have a much more narrow food preference, but the Burmese python is a generalist feeder and will eat birds, mammals, small reptiles, whatever comes its way. That's one reason why this animal has been successful," explained Dr. Jacobson, who taught zoologic medicine for more than three decades at the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine until his recent appointment as professor emeritus.

Science says

When the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced its rules concerning constrictor species in January, Interior Secretary Salazar cited a 2009 U.S. Geological Survey analysis—"Giant constrictors: biological and management profiles and an establishment risk assessment for large species of pythons, anacondas, and the boa constrictor."

The 302-page Constrictor Report, as it is known, classified Burmese pythons, Northern and Southern African pythons, boa constrictors, and yellow anacondas as high-risk invasive species for the following reasons: The snakes put large portions of the country at risk, constitute a significant ecologic threat, or are popular within the reptile trade. Medium-risk species are the reticulated python, DeSchauensee's anaconda, green anaconda, and Beni anaconda, the report stated.

The USGS risk analysis identified the pet trade as "the only probable pathway by which these species would become established in the United States." The recent snake bans are meant to mitigate the invasive-constrictor threat by squeezing off channels through which a person can legally possess a giant snake. The other five constrictors in the report also face possible listing under the Lacey Act.

The Constrictor Report followed up on a 2008 paper in which USGS scientists used a climate-based distribution model to show a sizeable portion of the U.S. mainland is vulnerable to feral Burmese python habitation. Regions where the climate may be suitable to support python populations, according to the USGS study, include the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coasts and range from Delaware to Oregon, including most of California, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. By 2100, the report said feral pythons may be able to expand their range to parts of Washington, D.C., and Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York.

Two subsequent studies challenge the premise that Florida's Burmese python can survive far from the snake's current subtropical home, however.

Using ecologic models that accounted for climatic extremes and averages, researchers at The City University of New York found the only suitable habitat for the python is in South Florida and far-south South Texas. Moreover, future climate models based on global warming forecasts indicate the python's current U.S. habitat and native range will actually decrease. A related study by scientists with the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Wildlife Research Center found evidence suggesting Burmese pythons in Florida lack cold-weather survival instincts necessary to flourish elsewhere in the United States.

USGS scientists subsequently evaluated the methodology of the CUNY study. The models used to challenge the potential for python colonization in the United States may not identify all sites at risk of habitation, according to the paper they published in 2011. A more biologically realistic model less prone to statistical problems may reveal a larger geographic range where pythons could become established, the scientists concluded.

When the Senate was reviewing legislation in 2009 to designate constrictors as injurious animals, nine herpetologists and veterinarians wrote leading members of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works with concerns about the Constrictor Report. They questioned the USGS scientists' methods as well as the peer-review process the report underwent. The accuracy of the risk assessment model the report authors used was called into doubt; critics wrote the model resulted in a "gross overstatement" of the potential habitat for the snake species.

In their letter, critics noted "a pervasive bias" throughout the Constrictor Report. "There is an obvious effort to emphasize the size, fecundity, and dangers posed by each species; no chance is missed to speculate on negative scenarios. The report appears designed to promote the tenuous concept that invasive giant snakes are a national threat. However, throughout the report there is a preponderance of grammatical qualifiers that serve to weaken many, if not most, statements that are made," the letter states.

The letter concludes with a request for the Senate committee to view the USGS analysis not as an authoritative scientific publication but as a report drafted with a predetermined policy in mind.

In addition to his post at the University of Florida, Dr. Jacobson chairs the Association of Reptilian and Amphibian Veterinarians' Legislative and Animal Welfare Committee. One of three ARAV officials who signed the letter to the Senate committee, Dr. Jacobson isn't opposed to listing certain large constrictors as injurious wildlife—unless the science for doing so is flawed, which he believes to be the case.

"The perception is that certain politicians used the USGS report to justify their position without really understanding what was being presented in the report," Dr. Jacobson explained.

Robert Reed, PhD, is a USGS invasive species scientist and herpetologist who co-authored both agency studies warning about the giant-snake threat. He's spent the past six years researching the brown tree snake, which, within four decades of its arrival in Guam, devastated much of the island's native wildlife. More recently, he's turned his attention to the Burmese python and is investigating the snakes' ecologic impact in South Florida and exploring ways of managing their numbers.

Dr. Reed knows what critics are saying about him. "I'm accused by the pet trade of pushing the 'injurious' listing to get loads of research dollars," he said. "But I've never given any public opinion on the utility of this listing, and it doesn't result in any more research dollars whatsoever."

He's equally dismissive of allegations he wants to criminalize snake ownership, as is his USGS colleague Gordon Rodda, who co-wrote both USGS invasive-snake studies.

"Gordon and I own or have owned giant constrictors, and we say so in the first chapter of the Constrictor Report. We think they're beautiful animals," he explained. "To suggest we're anti–snake ownership is really silly on the face of it."

"On the science issues," Dr. Reed continued, "I'm happy to let the peer-reviewed papers speak for themselves. There's an increasing body of evidence to suggest that these snakes are a big problem in southern Florida and that there are several other (constrictor) species that have climates in their native range that suggest they could become established in the U.S."

Assessing the damage

Burmese pythons have flourished in South Florida since the 1980s, yet no one could say with certainty how they were affecting the ecosystem. Then in late January, a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences made a correlation between severe mammal declines and the proliferation of pythons in Everglades National Park.

Dr. Reed was a co-author of the report, in which researchers state raccoons, rabbits, and opossums have almost entirely vanished from the southernmost regions of the Everglades, where pythons have been established the longest. Populations of raccoons in that part of the park dropped 99.3 percent, opossums 98.9 percent, and bobcats 87.5 percent. Marsh and cottontail rabbits and foxes were no longer seen at all, according to the study.

Data were gathered during repeated, systematic nighttime road surveys within the Everglades, with researchers counting live and roadkill animals. Surveys from 2003-2011 of nearly 39,000 miles of road were analyzed and compared with results of similar surveys peformed along the same roadways in 1996 and 1997, before pythons were recognized as established in the park.

Researchers also surveyed ecologically similar areas north of the Everglades where pythons have not been discovered. In those areas, "mammal abundances" were similar to those reported in the park before pythons proliferated. At sites where pythons have only recently been documented, however, mammal populations were reduced, though not to the dramatic extent observed within the park where pythons are well-established.

"The magnitude of these (mammal) declines underscores the apparent incredible density of pythons in Everglades National Park and justifies the argument for more intensive investigation into their ecological effects as well as the development of effective control methods," said lead study author Michael Dorcas, PhD, a professor in the Biology Department at Davidson College in North Carolina.

"Such severe declines in easily seen mammals bode poorly for the many species of conservation concern that are more difficult to sample but that may also be vulnerable to python predation," added Dr. Dorcas, who co-wrote "Invasive pythons in the United States: Ecology of an introduced predator." Published in 2007, the book suggested Burmese pythons could spread over much of the United States.

Shortly after the NAS Proceedings paper became available, The Huffington Post ran an article written by Frank Mazzotti, PhD, one of the study co-authors, in an attempt to clarify what the report does and doesn't say. The data do not show Burmese pythons caused the mammal declines, only that the snakes' occurrence is coincident with the decreases, wrote Dr. Mazzotti, an associate professor of wildlife ecology at the University of Florida.

"I liken what we did to a grand jury investigation," he wrote. "We amassed the available evidence and asked if it was sufficient to demonstrate that a crime had occurred (mammal populations had declined) and to suggest that pythons could be responsible (they had motive, means, and opportunity). An indictment was handed down. That does not mean the pythons are guilty. It does mean we need to go to trial."

The next step, according to Dr. Mazzotti, is to "design a study that evaluates the presence of the pythons with the absence of mammals in relation to differences and changes in habitat, hydrology, and other biological components." The study should be a "high priority for funding," he wrote, because it could go a long way toward identifying what's behind the mammal die-off in the Everglades.

"(W)hat happens if we are wrong and something else caused mammal populations to decline?" Dr. Mazzotti wrote. "Because if it is not pythons (and it might not be), something else is wrong in an ecosystem that we are spending billions of dollars to restore, and we need to know what that is."