Closing of U.S. horse slaughter plants still reverberates

After four years without domestic horse slaughter facilities in operation and a thorough study of the results, one thing is clear: the same number of horses from the United States, if not more, are being killed for their meat every year.

According to a recently released report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the plant closures have shifted the slaughter horse market to Canada and Mexico and driven down the sale prices of lower-grade horses. They've also worsened an already bad welfare situation by forcing horses to travel long distances to slaughter, often in unregulated trips.

Since fiscal year 2006, Congress has annually prohibited the use of federal funds to inspect horses destined for food, effectively halting domestic slaughter. With the cessation of domestic slaughter in 2007, Congress directed the GAO to examine horse welfare.

The organization's 68-page report, "Horse Welfare: Action Needed to Address Unintended Consequences from Cessation of Domestic Slaughter," came out June 22, more than a year after its scheduled release date (see JAVMA, Nov. 1, 2009).

The GAO examined the effects, if any, of the plants' closures on the U.S. horse market; the impact of such market changes on horse welfare and on states, local governments, tribes, and animal welfare organizations; and the challenges, if any, to the Department of Agriculture's oversight of the transport and welfare of U.S. horses exported for slaughter.

From its analysis, the GAO recommended that Congress reconsider restrictions on the use of federal funds to inspect horses for slaughter or institute a permanent ban on horse slaughter in the U.S. Further, the agency recommended that the USDA issue a final rule to protect horses during more of the transportation chain to slaughter, and consider ways to better leverage resources for compliance activities.

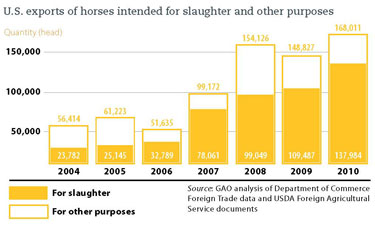

Worsening horse welfare

According to the GAO, from 2006 through 2010, the number of horses exported from the U.S. to Canada for slaughter increased by 148 percent and the number exported to Mexico increased by 660 percent. As a result, nearly the same number of U.S. horses were transported to Canada and Mexico for slaughter in 2010—almost 138,000—as were slaughtered before domestic slaughter ceased in 2007. For reference, 104,899 horses were slaughtered in 2006, the last full year of domestic slaughtering operations, according to the report.

Meanwhile, horse prices have declined since 2007, mainly for the lower-priced horses that are more likely to be bought for slaughter. GAO analysis of horse sale data estimated that closing domestic horse slaughtering facilities substantially and negatively affected lower- to medium-priced horses by 8 to 21 percent.

Although comprehensive, national data are lacking, state, local government, and animal welfare organizations report a rise in investigations for horse neglect and more abandoned horses since 2007. For example, Colorado data showed that investigations for horse neglect and abuse increased more than 60 percent, from 975 in 2005 to 1,588 in 2009.

All of the 17 state veterinarians who were surveyed said that horse welfare in their states had generally declined, as evidenced by a reported increase in cases of horse abandonment and neglect. They most frequently cited two factors that contributed to the decline in horse welfare—the halt of domestic slaughter in 2007 and the economic downturn.

Local, tribal, and horse industry officials agreed with the state veterinarians' conclusions, but representatives from some animal welfare organizations said that owners who abandon horses are going to do so regardless of whether they have the option of domestic slaughter.

The GAO report also determined that counties and animal welfare organizations bear the costs of collecting and caring for abandoned horses, while county governments generally bear the costs of investigating reports of neglect. These county officials said horse rescue operations in their states are at, or near, maximum capacity, with some taking on more horses than they can properly care for.

News reports have told of horse rescue groups in California, Florida, New York, and West Virginia that had their animals seized by local authorities because they were not properly caring for them, and others in New Hampshire and Pennsylvania that have closed because of financial difficulties.

Requests for restored funding

The USDA faces its own challenges as it oversees the welfare of horses during transport to slaughter.

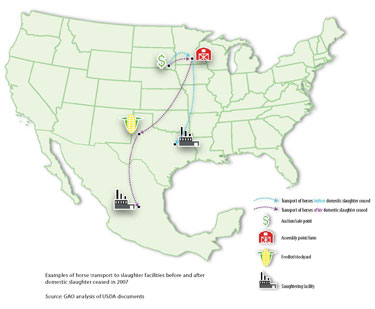

Current transport regulations apply only to horses transported directly to slaughtering facilities. A 2007 proposed rule would more broadly include horses moved first to stockyards, assembly points, and feedlots before being transported to Canada and Mexico (see JAVMA, Dec. 15, 2007), but delays in issuing a final rule have prevented the USDA from protecting horses during much of their transit to slaughtering facilities. The report also found that many owner/shipper certificates, which document compliance with the regulation, are being returned to the USDA without key information, if they are returned at all.

The GAO recommended that Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack direct Dr. Gregory L. Parham, administrator of the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, to issue as final a proposed rule to amend the Commercial Transportation of Equines to Slaughter regulations to define "equines for slaughter" so that USDA's oversight and the regulation's protections extend to more of the transportation chain.

Further, annual legislative prohibitions on the USDA's use of federal funds for inspecting horses since fiscal year 2006 have hindered the department's ability to improve compliance with—and enforcement of—the transport regulations. The report recommended that Congress consider allowing the USDA to again use funds to inspect U.S. horses being transported to slaughter. This would allow the USDA to better ensure horse welfare and identify potential violations of the CTES regulation.

And, the report suggested that Congress consider allowing the USDA to again use appropriated funds to inspect horses at domestic slaughtering facilities, as authorized by the Federal Meat Inspection Act. A competing recommendation asked that Congress consider instituting an explicit ban on the domestic slaughter of horses and export of U.S. horses intended for slaughter in foreign countries.

Finally, the GAO noted that U.S. horses intended for slaughter are now traveling substantially farther distances to reach their final destination, where they are not covered by U.S. humane slaughter protections. The USDA lacks the staff and resources at borders and foreign slaughtering facilities that it once had in domestic facilities to help identify problems with shipping paperwork or the condition of horses before they are slaughtered.

Groups react

The American Association of Equine Practitioners president, Dr. William A. Moyer, issued a statement the same day the report was released. He said the association agrees with the GAO's conclusions regarding the unintended consequences of the domestic slaughter ban.

The AAEP does not believe horse slaughter is the ideal solution for addressing the large number of unwanted horses in the U.S. That said, if a horse owner is unable or unwilling to care for the horse and no one else will assume responsibility, the AAEP considers humane slaughter to be an acceptable alternative to suffering, inadequate care, or abandonment.

Regarding the GAO's recommendations, Dr. Moyer said the lack of federal funding for the USDA's transport oversight program cripples the agency's ability to properly protect horses that are shipped to processing facilities.

"Eliminating the funding for inspecting this population of horses has, as outlined by the GAO report, decreased the welfare of these horses. Our association supports the return of funding to the USDA. The AAEP feels it is equally important that the USDA quickly issue its final rule on transport regulations so the agency's oversight will extend to more of the transportation chain for horses shipped to slaughter," he said.

Dr. Moyer added, "If Congress pursues the option of banning the processing of U.S. horses without the appropriate funding and infrastructure in place to appropriately care for these animals, this action may only amplify the negative welfare implications for this highly vulnerable population of horses."

The AVMA, too, supports many of the recommendations that came from the report, including providing more resources to enforce the CTES regulations and stronger penalties for transporters who do not comply, and issuing a final rule to amend the regulations so that oversight protection extends throughout the transportation chain. The AVMA also is advocating for the phaseout of double-decker trucks for the transportation of horses.

The Humane Society of the United States supports strengthening the laws and banning exports, noting that there already is proposed legislation aiming to do just that. The American Horse Slaughter Prevention Act (S.1176) was introduced in June by Sens. Mary Landrieu and Lindsey Graham. In the same month, Sens. Mark Kirk and Frank Lautenberg introduced S. 1281, the Horse Transportation Safety Act of 2011. If passed, the latter bill would prohibit interstate transport of horses in double-decker trailers for any reason.

Michael Markarian, president of the Humane Society Legislative Fund, argued in a June 23 blog post: "Industries that want to profit from horse slaughter and the export of American horse meat to Europe and Asia will claim that we need to reopen horse slaughter plants in the U.S. so that horses are not traveling long distances to Canada and Mexico, and that Congress should fund USDA oversight of horse slaughter, potentially adding millions of dollars to the federal budget and distracting agency inspectors from other food safety responsibilities. But when a handful of slaughter plants did operate in the U.S., horses still traveled long distances across the country in dangerous double-decker trucks, and the transport and slaughter processes involved were inherently inhumane."

To read more about unwanted horses and horse slaughter, go to "Frequently Asked Questions" or following link "News articles and other resources regarding unwanted horses and horse slaughter."