We're all in this together

When educators mention campus climate, they aren't referring to weather patterns.

No, they are talking about the prevailing conditions that characterize an institution and how welcoming it is to individuals from underrepresented minority groups. Campus climate is part of how veterinary schools and colleges support and mentor underrepresented students, how they recruit these students, the ability of these graduates to do their jobs well, and the experience and productivity of all students and faculty in general. All of these factors can affect a college's quality and value and its ability to carry out its mission, said Frances E. Kendall, PhD, at the 18th Iverson Bell Symposium March 11-12 in Alexandria, Va. This was the first year the symposium was incorporated into the overall AAVMC Annual Conference.

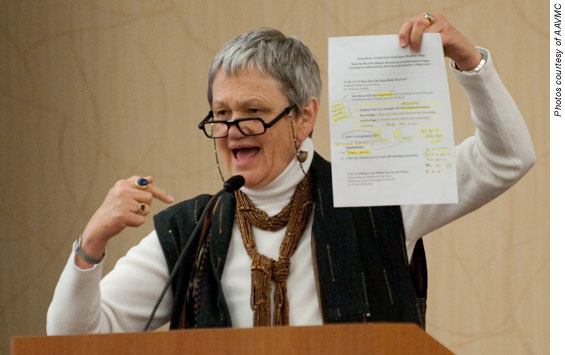

Dr. Kendall, a national consultant on organizational change, diversity, and "white privilege," gave a talk at the meeting, titled "Using Climate Surveys to Support Creating an Authentically Diverse and Inclusive College Culture." She spurred discussion on the current reality at institutions, what can be done to effect positive change, and what individuals are already doing to improve their campus climates.

Room for improvement

Although no comprehensive data currently exist on campus climate at all 28 veterinary schools and colleges in the U.S., a survey is currently under way (see article).

Even while results of this survey are pending, it is clear that veterinary schools and colleges have come up short with regard to at least one indicator of a positive campus climate—the numbers of students, faculty, and administrators from underrepresented minorities.

According to the 2010 AAVMC comparative data report, only 1,038 of the 10,115 students currently attending veterinary schools and colleges in the U.S., or just over 10 percent, are from underrepresented minorities.

The number of faculty members from underrepresented minorities in the U.S. schools is 535, which represents just over 14 percent of all faculty members. Among deans of the 28 U.S. veterinary schools and colleges, only three are from historically underrepresented populations, and only five are women.

One of the goals in the AAVMC's strategic plan is to, by 2014, increase the number of underrepresented minority students by 35 percent, compared with the 2009 figure of 1,287, and increase the number of underrepresented minority faculty members by 20 percent.

"We will have to increase that number to 1,766 (underrepresented minority) students, given the numbers, which is about 92 students per year, or three students per college per year," said Dr. Willie M. Reed, dean of the Purdue University School of Veterinary Medicine, at the meeting. If we really believe that diversity and inclusion are necessary for our profession, we must set the bar higher, and we must work harder than ever before and renew our commitment for those who choose careers in our profession."

Who's in charge here?

So who's responsible for a better campus climate? Essentially, it's everyone, according to Dr. Kendall.

"Often the expectation is faculty of color or students of color will take care of race in the college—that they will be on diversity committees and make changes and do all things pertaining to race, and the white faculty and administration and students don't have that responsibility," she said. "Think of how your life would be different if all white students thought you were the person to support their experience there because you are white."

The leadership, of course, arguably plays the largest part in creating a positive environment, by supporting change and by being accountable for the campus climate. According to Dr. Kendall, campus climate is informed by, and reflected in, the following five primary dimensions of a university:

- Institutional action, including who is appointed to hiring and recruiting committees.

- Research and training, including expectations of faculty.

- Structural diversity, including how policies and procedures are crafted.

- Intergroup interaction, including opportunities provided for students to work with people who are different from them.

- Campus' socio-historical context.

Although the university's history cannot be altered, other areas can be to create a better campus climate, at least to a certain extent.

"In the academic world, as we know, somebody at the top says you will do this, and the faculty decides whether they want to do it or not," Dr. Kendall said. "Every faculty member needs to be questioned about how they deal with differences in the classroom. It has to be a part of the hiring process."

Dr. John W. Tyler, associate professor of small animal medicine at Western University of Health Sciences College of Veterinary Medicine, advised at the meeting not to make it a personal issue in working with current faculty.

"Make it a challenge faculty can strive for instead of saying, 'You're doing it all wrong,'" he said.

Leading by example

A magic formula to create the perfect climate may not exist, but some veterinary schools and colleges have seen small victories at various levels.

Dr. Ronnie G. Elmore, associate dean for academic affairs and admissions at the Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine, said he's privileged to work in an environment that promotes diversity not only university-wide but also throughout the regent system. K-State's associate provost and president are devoted to diversity, and all regent schools in Kansas are part of the Michael Tilford Conference on Diversity and Multiculturalism, which involves getting together yearly to talk about diversity.

Dr. Elmore is also part of the Safe Zone community network of trained faculty and students who are available to listen to and support students. He helps connect students with campus resources to address problems they face, particularly related to sexual violence, hateful acts, and discrimination.

Dr. Jacquelyn Pelzer, director of admissions and student services at Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine, said this year the college started implementing more diversity training in the pre-clinical curriculum. This included a two-hour lecture on diversity for first-year students.

Even though the experience didn't go quite as planned, Dr. Pelzer said she learned some valuable lessons from the experience.

For example, the best way to structure the lecture is to have clear-cut goals as to why teaching diversity is important to the program, to share that with the lecturer, and to begin the lecture by discovering what classmates have in common, then easing into more challenging topics. And, always have a moderator.

"I learned it's a painful yet necessary process. We will continue to implement (diversity) topics in the curriculum, but with every new course there are growing pains," she said.

Students themselves have taken the initiative in creating an inclusive environment at their veterinary schools and colleges.

The Veterinary Students as One in Culture and Ethnicity organization has 14 chapters throughout the United States and in the Caribbean. The original chapter, at Cornell University, remains quite active, said Kevin Render, a second-year veterinary student and a member of VOICE.

The group had three goals this year: To look back on what has worked in the past and what hasn't, reincorporate the things that did have a lot of participation, and host an event every month. The group found that VOICE at Cornell traditionally hosted potlucks that had proved popular.

So this year, VOICE celebrated Hispanic Heritage Month in September and Black History Month in February, and the group will observe Asian-Pacific Islander Month in May.

"It's a push where everything doesn't have to be educational, but an experience. Exposing those things to veterinary students in general—like different cultures—is great," Render said.