Another ballot initiative increases housing size for farm animals

As consumers demand to know more about the origin of their foods, the trend toward less-restrictive housing for farm animals has accelerated in recent years.

Much of the change has come through ballot initiatives, a tactic pioneered by the Humane Society of the United States. So far, a dozen states have banned or restricted confinement housing for at least one production animal species. Most recently, on Nov. 6, 2018, California voters passed a ballot measure by 61 percent that requires all eggs sold in the state to come from cage-free hens by 2022.

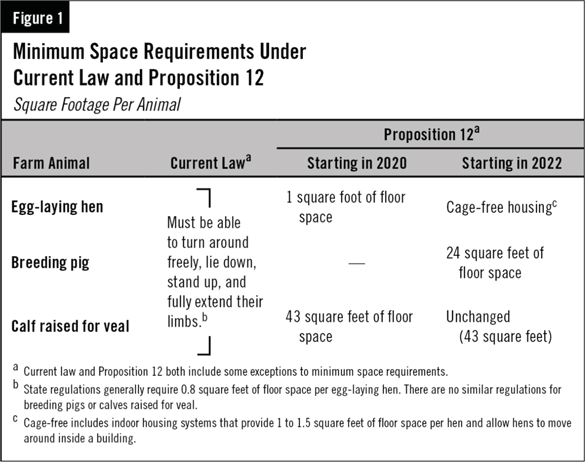

Proposition 12 also sets new minimum size requirements for the pens that farmers use to house breeding pigs and calves raised for veal, and it bans the sale in California of products from hens, calves, and pigs raised in other states if the animals were confined to areas below those minimum size requirements.

"Veal production in California is virtually non-existent, hog production is very small, and sow gestation crates are not known to be used in California," according to a 2009 white paper on animal welfare from the University of California Agricultural Issues Center following passage of a 2008 California ballot initiative to restrict confinement of farm animals. Therefore, the statute was "important only to regulate the housing conditions for egg-laying chickens that are kept in cages" and produce a majority of the state's eggs.

The Legislative Analyst's Office, the California legislature's nonpartisan fiscal and policy adviser, said Proposition 12 will likely result in an increase in prices for eggs, pork, and veal partly because farmers will have to remodel or build new housing for animals.

It could also cost the state as much as $10 million a year to enforce the provisions and millions of dollars more a year in lost tax revenues from farm businesses that choose to stop or reduce production because of higher costs, the office said.

A series of studies on hen confinement housing systems found that no one system is perfect and that there are often trade-offs among animal welfare, environmental impact, food affordability, food safety, and worker health and safety.

Devil is in the details

A decade ago, California voters approved a previous ballot initiative—Proposition 2—that required the state's producers to make major alterations to livestock housing systems by 2015. It was the furthest-reaching law for farm animals in the country at the time, but was criticized for, among other things, its vague language.

Proposition 2 said egg-laying hens, veal calves, and pregnant sows in California must have enough room to lie down, stand, turn around, and fully extend their limbs, effective in 2015. A 2010 amendment required all eggs sold within California, regardless of where they are produced, to comply with the new law.

Related state regulations came in 2013 specifying that in-state and out-of-state egg producers who sell eggs in California must provide at least 116 square inches of space for each hen living in an enclosure of nine or more hens. Enclosures with fewer birds need to have progressively more space for each bird, with 322 square inches of space required for a hen living alone.

Now with Proposition 12's passage, the requirements go further. The ballot initiative requires that, starting in 2020, calves confined for production have at least 43 square feet of usable floor space, while breeding pigs must be provided at least 24 square feet of floor space in their pens starting in 2022.

Starting in 2020, egg-laying hens must be given 1 square foot of floor space each on the way to being cage-free by 2022.

Proposition 12 made the California Department of Food and Agriculture and the California Department of Public Health responsible for the measure's implementation. Violations are considered misdemeanors.

HSUS introduced and sponsored both Proposition 2 and Proposition 12 with the support of several animal welfare groups, including the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Farm groups that opposed Proposition 12 included the Association of California Egg Farmers, which issued the following statement: "With this new initiative now calling for full compliance by the end of 2021, HSUS is reneging on the original agreement and this expedited timeline may result in supply disruptions, price spikes and a shortage of eggs for sale."

"Vote-buy" paradox

Most U.S. hens are currently housed in conventional cage environments. As of January 2018, organic and cage-free egg production accounted for 16 to 18 percent of the total laying flock, according to the Egg Industry Center, and 10 to 15 percent of market share.

In response to Proposition 2, stores in California initially imported more eggs from other states. According to a recent study, shortly after the new law took effect in 2015, the price of eggs increased by more than a third, though by fall 2016, the authors estimated that prices were 9 percent higher than they would have been without the law (Am J Agric Econ 2018;100:649-669).

One of the authors of the study, Jayson Lusk, PhD, an agricultural economist at Purdue University, said an increasing share of egg production nationwide is coming from cage-free production systems. At the same time, more than 200 grocery stories and food companies have made commitments to offer only cage-free eggs by 2025. If these pledges are upheld, the industry will go from 16 to 18 percent cage-free to 75 or 80 percent in about six years. But that's a big "if."

"Are they going to uphold pledges? That's far from certain," Dr. Lusk said. "While early on … there was an uptick, but afterward pledges slowed down in the conversion of egg producers because retailers weren't moving product as quickly as they anticipated. I get the sense from the producer side that they won't convert until there's incentive for them to do so, or continue converting."

Lusk calls it the "vote-buy" paradox when people vote to ban the sale of a product they routinely buy. He said: "It's a conundrum. It's not as if cage-free eggs aren't available in most locations—they are—but when people have to put money where their mouth is, they don't pay the higher price."

Lusk says another potential impact of Proposition 12 that's getting less attention is what is going to happen to the supply of pork in the state. "California essentially imports pork from other states, and this law would ban the sale of pork from a gestation crate system, which is still the predominate mode of production in the U.S.," he said. "What's going to happen? I could imagine, at least in the short term, shortages if they can't convince suppliers to switch (housing systems)."

Pros and cons

For all of the emphasis put on switching to this new housing system, its definition and even impact still haven't solidly been determined or well understood.

While many companies have made the commitment to cage-free egg production, very few of them defined "cage-free" when they made the announcement, said Dr. Larry Sadler, vice president of animal welfare for the United Egg Producers, at the Pig Welfare Symposium in late 2017, as quoted by Feedstuffs.

The UEP announced in 2017 that it had developed its own definition for cage-free egg production: "Cage-free eggs are laid by hens that are able to roam vertically and horizontally in indoor houses and have access to fresh food and water. Cage-free systems vary from farm to farm and can include multi-tier aviaries. They must allow hens to exhibit natural behaviors and include enrichments such as scratch areas, perches and nests. Hens must have access to litter, protection from predators and be able to move in a barn in a manner that promotes bird welfare."

But does cage-free equate to better animal welfare?

A multidisciplinary public–private partnership was formed to carry out a Coalition for Sustainable Egg Supply project to obtain research-based information on this topic. The goal of this commercial-scale study of housing alternatives for egg-laying hens was to understand the sustainability impacts of three housing systems for laying hens—cage-free aviaries, enriched colony cages, and conventional cages.

Investigators from Michigan State University, the University of California-Davis, Iowa State University, and the Department of Agriculture's Agricultural Research Service participated in the research. They evaluated the systems' potential impacts on food safety, the environment, hen health and well-being, worker health and safety, and food affordability.

The resulting studies showed there are positive and negative impacts as well as trade-offs associated with each of the three hen housing systems relative to each of the five areas. According to a summary of research results:

- Hens kept in the cage-free—or aviary—environment were more likely to develop hypocalcemia than those in conventional cages or enriched colony cages, and cage-free hens that died were more likely to have been caught in the system, cannibalized, or pecked extensively than conventional-cage or enriched-colony hens. But cage-free pullets had better bone quality of the humerus and tibia, though they also had more keel bone damage. Between 9 and 21 percent of flights in the aviary ended in failed landings, which could have contributed to the higher level of keel bone breakage.

- Hens in all housing systems shed Salmonella organisms at a similar rate.

- Daily mean indoor ammonia concentrations, dust levels, and particulate matter emissions were all highest in the aviary house and lowest in conventional cage and enriched colony houses.

- While working in the aviary house, workers were exposed to significantly higher concentrations of airborne particles and endotoxin than when working in conventional cage and enriched colony houses; exposures in conventional cage and enriched colony houses were similar to one another.

- The aviary system had a total cost per dozen eggs that was 36 percent higher than the cost for eggs produced with the conventional cage system; the enriched colony system had a total cost per dozen eggs that was 13 percent higher than the cost for eggs produced with the conventional cage system.

Read the full results of the research.

Related JAVMA content:

Egg rules endure challenges (April 1, 2015)

California voters call for changes in livestock housing (Dec. 1, 2008)

AVMA weighs in on California livestock housing referendum (Oct. 1, 2008)