Suicide trend in the profession stretches back decades

Although the past few years have seen greater awareness of mental health issues and the incidence of suicide within the U.S. veterinary profession, evidence of the suicide mortality rate being higher among veterinarians than in the U.S. general population goes back even further.

An all-cause mortality analysis published in 1982 studied 5,016 white male veterinarians who died from 1947-77, using obituary listings published in JAVMA and state death certificates. The study showed that the proportionate mortality rate from suicide in this group was 1.7 times that of the U.S. general population.

Now come data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health on mortality rates from suicide among 11,620 veterinarians who died from 1979-2014. Researchers announced their findings at the 2018 Veterinary Wellbeing Summit, held April 15-17 in Schaumburg, Illinois, and sponsored by the AVMA, Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges, and Zoetis. They concluded that male veterinarians were 2.1 times as likely and female veterinarians were 3.5 times as likely to die from suicide as were members of the U.S. general population, and these higher suicide mortality rates extended the entire 36-year period. The full results will be published this year or next.

"In this study, your mortality from suicide among veterinarians has been high for some time," said Randall Nett, MD, public health service medical officer for NIOSH, who gave the presentation at the summit. "It's a complex problem, and hopefully we can work as a team to lower suicide mortality among veterinarians."

Study results

This latest study by the CDC, led by Dr. Suzanne E. Tomasi, an Epidemic Intelligence Service officer at NIOSH, sought to explore the historical trends for suicide among U.S. veterinarians, particularly as the profession has shifted from majority male to female since the last analysis.

The data set for this study was created by linking data from two sources: the AVMA and the CDC. The AVMA maintains a data set of all known U.S. veterinarians who have died, through obituary information submitted to JAVMA and life insurance policies. These sources provided age, sex, race, clinical positions, and species specialization. Within the CDC is the National Center for Health Statistics, which maintains the National Death Index. The NDI provided underlying cause of death information for the deceased veterinarians.

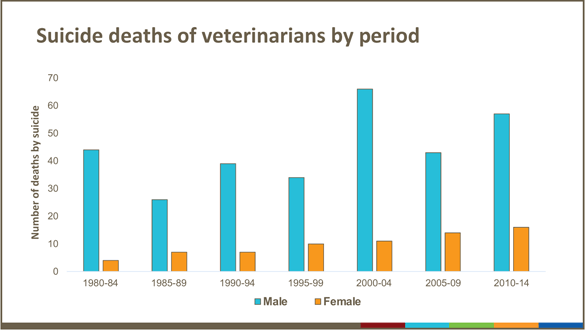

The cause of death for 398 (3 percent) of these 11,620 veterinarians was attributed to suicide. Of the 398 who died from suicide, 326 (82 percent) of them were men and 72 (18 percent) were women. The median age was 57 years for men and 42 years for women. Seventy-five percent of those with known species specialization worked in small animal medicine.

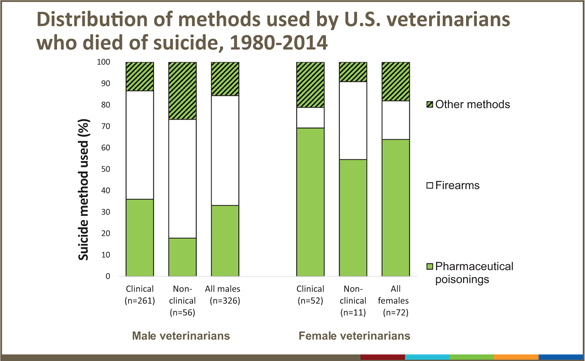

When comparing the methods of suicide between the general U.S. population and veterinarians, the researchers found notable differences.

Fifty-one percent of male veterinarians who committed suicide used firearms, and 32 percent used poisoning, compared with 18 percent of female veterinarians who used firearms and 64 percent who used poisoning.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Among the general population, use of firearms was the most common method. Yet in the study population, although firearms were still the most commonly used method, poisonings were higher than in the general population.

Fifty-one percent of male veterinarians who committed suicide used firearms, and 32 percent used poisoning, compared with 18 percent of female veterinarians who used firearms and 64 percent who used poisoning. "We can't really break out euthanasia drugs in poisonings, but barbiturates are a substantial part," Dr. Nett said.

For both male and female veterinarians, those in clinical positions more often used pharmaceutical poisoning than did those in nonclinical positions.

Dr. Tomasi, in a May 2 CDC webinar, pointed to the following factors for the high suicide proportionate mortality rate among U.S. veterinarians:

- Demands of practice such as long work hours and work overload.

- Practice management responsibilities.

- Client expectations and complaints.

- Knowledge of euthanasia procedures and training to view euthanasia as a normal and acceptable method to relieve suffering

- Ever-increasing educational debt-to-income ratio.

- Poor work-life balance

- Access to controlled substances such as euthanasia solution and the pharmacological training to calculate a lethal dose.

Prevention strategies

Dr. Nett said NIOSH's hierarchy of controls—a framework used to make recommendations on methods of controlling occupational hazards to help prevent occupational illnesses and injuries—could be used in this situation to help guide suicide prevention measures. Examples of possible administrative controls could include scheduling shorter work shifts and restricting access to euthanasia solution.

Dr. Tomasi said suicide prevention needs to extend beyond the workplace. This can be done by taking the following steps:

- Applying evidence-based suicide prevention strategies throughout the profession.

- Improving U.S. veterinarians' awareness of suicide prevention resources.

- Collaboration among multiple stakeholders in the profession.

- Using data to evaluate trends and effectiveness of suicide prevention activities.

Other possible activities include studying work-related factors that led to veterinarians considering or even attempting suicide and conducting a veterinary clinic assessment on how well-being practices are being integrated into typical clinics, Dr. Nett suggested.

Current suicide rate data

Thus far, data on U.S. veterinarians' mental health and well-being have shown mixed results.

A 2014 survey by the CDC found that veterinarians were at higher risk for mental illness and suicide than the general population. However, a study conducted by Merck Animal Health in 2017 concluded that veterinarians as a group don't experience psychological distress at rates notably higher than the general population, although the study did find that to be the case for young veterinarians.

That said, veterinarians abroad seem to have a high prevalence of risk factors for suicide, too. Studies from the United Kingdom indicate that veterinarians have a proportionate mortality rate from suicide that is four times that of the general population and two times that of other health care providers (Vet Rec 2010;166:388-397). In Norway, male veterinarians had a suicide mortality rate that was four times that of the general population (Psychol Med 2005;35:873-880).

And in Australia, veterinarians had a mortality rate that was also four times that of the general population (Aust Vet J 2008;86:114–116).

Related JAVMA content:

Mental health, well-being problem serious, not dire: study (Feb. 15, 2018)

Study: 1 in 6 veterinarians have considered suicide (April 1, 2015)