Safety first

Dr. Aimee Eggleston was a few months shy of completing an internship at a large, private equine practice outside Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2010 when she received an emergency call about a colicky horse. She jotted down the address, hopped in her truck, and off she went.

Experienced interns at the practice were expected to handle emergency calls alone as a way of honing their skills. Dr. Eggleston was 27 at the time, and she thought nothing of traveling by herself to remote locations at all hours. It's what an equine veterinarian does, she told herself. Dr. Eggleston watched the daylight fade as she followed an endless series of back roads deeper into the Virginia countryside. When she finally reached the location, she saw a colt tied to a tree near a house where several young men sat on a porch, obviously drunk.

"I remember it, even 19 years later. I had no cell service, no way of communicating, nothing. What do I do?" Dr. Eggleston recalled. "Protecting yourself from being assaulted isn't talked about in veterinary school. It's certainly something you think about as a woman, but I was there as a veterinarian."

"There's a lot pressure to just suck it up and do it, and so I did," Dr. Eggleston said. She treated the horse without incident, relaxing only after a woman emerged from the house.

Protecting yourself from being assaulted isn't talked about in veterinary school. It's certainly something you think about as a woman, but I was there as a veterinarian.

Dr. Aimee Eggleston, equine practice owner

Today, Dr. Eggleston co-owns a solo equine-exclusive practice in Woodstock, Connecticut, with her husband, Tim, servicing clients in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts. In hindsight, Dr. Eggleston says she was foolish to put herself in a potentially dangerous situation and is careful now not to make the same mistake.

"Nothing happened to me, thankfully," she said, "but that was one of the first times I really felt just how bad it could be."

Whistling past the graveyard

Resources for veterinarians on workplace safety are available from governmental agencies and professional organizations, notably the National Institute for Occupational Safety Health of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the AVMA. That information, while valuable, mostly offers ways of preventing on-the-job injuries, not protecting oneself from violent crime.

A likely explanation for the lack of personal safety resources is low demand. Phil Seibert, a veterinary clinic safety consultant and author of The Veterinary Safety and Health Digest, says most veterinarians don't believe they will be the victim of a crime and, therefore, don't take the necessary precautions. A former U.S. Army veterinary technician with more than two decades of experience in veterinary hospital security, Seibert noted that personal safety and hospital security are rarely offered as continuing education for veterinary professionals.

"It's often taken for granted and not given much thought past 'Lock the doors at the end of the day' until something happens. Then everyone is shocked that we missed the signs that something was amiss," he said.

According to Dr. Linda Ellis of the AVMA PLIT, a mean of 91.6 burglary claims have been filed annually with the Trust through the veterinary-specific business insurance program over the past 14 years; the average cost for these claims was just over $4,600. In rare instances, clinic robberies turn violent, as happened in September 1999, when Dr. Nirwan T. Thapar and his wife, Shashi, were murdered by two men at their Bladensburg, Maryland, veterinary hospital.

As Seibert explained, veterinary practices are like any other brick-and-mortar business, having to balance public accessibility, employee safety, and loss prevention. Eliminating risk entirely is a fool's errand, but Seibert says practices could go a long way toward making the workplace safer with a few simple steps. For instance, by installing security cameras inside and outside the clinic that are visible to both clients and staff. Strictly limiting access to the key for the controlled substances cabinet. Locking up the cash drawer.

"I'm appalled at how many veterinarians don't (see a) need to lock up the $100 or $200 change fund at the front desk," said Seibert, a firm believer in the adage that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. "Thinking 'I'd rather just let him take the money instead of tearing the place up looking for it' is like saying 'I'm going to put cat food on my front porch because I don't want wild animals sneaking into my house.' When you leave cat food on your front porch, it brings all the wild animals that may have gone somewhere else to your front door.

"I'm appalled at how many veterinarians don't (see a) need to lock up the $100 or $200 change fund at the front desk," said Seibert, a firm believer in the adage that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. "Thinking 'I'd rather just let him take the money instead of tearing the place up looking for it' is like saying 'I'm going to put cat food on my front porch because I don't want wild animals sneaking into my house.' When you leave cat food on your front porch, it brings all the wild animals that may have gone somewhere else to your front door.

"It's shortsighted to think they're going to take the money and nothing else. You're just inviting trouble."

Security on the road

What about veterinarians who work outside the confines of a clinic, who deal with clients on their farms and in their homes? How do they stay safe?

Dr. Erica Reinman is an ambulatory veterinarian and one of three female veterinarians at a mixed animal practice in Janesville, Wisconsin. She says daytime farm calls comprise the bulk of her large animal work, when a veterinary technician is likely to accompany her to assist and help restrain unruly animals if necessary. Emergency calls are another matter, as Dr. Reinman or whoever the on-call veterinarian is that night almost always responds to these alone.

While she has never been victimized during a call, Dr. Reinman has experienced what she described as "low-anxiety situations," when something about the visit unnerved her. "In those cases, I do what I need to get done and leave," Dr. Reinman explained. She said it's the kind of thing where she says, "Thank you very much; have a nice day," and she's gone.

The owners of the practice have authorized Dr. Reinman and her associates to refuse service if they feel unsafe, in which case the client will be referred to a 24-hour facility.

It's not only women veterinarians who think about their safety while on the road. Two days a week, Dr. Allen Cannedy makes farm calls in North Carolina's Piedmont region for his small ruminant and camelid mobile practice. As a 6-foot-tall, 240-pound African-American man, Dr. Cannedy says he has never felt threatened on the job. That's not to say he hasn't been on higher-than-normal alert, such as when he visited a new client who was flying a Confederate flag outside his house.

"Those are the scenarios more concerning to me as a black, male veterinarian in the South—driving in rural areas where I know that racism is alive and prevalent," explained Dr. Cannedy, who is also chief diversity officer for North Caroline State University College of Veterinary Medicine.

"I handle those situations professionally," he continued, "and basically go with the approach that someone has called me in their time of need for help, and that's what I'm there to provide: help in a way that's professional and to the point."

(Un)dependable technology

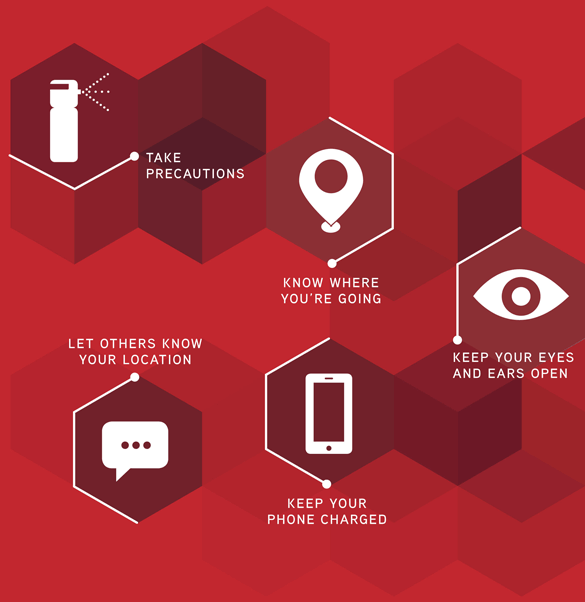

Seibert advises veterinarians on farm and house calls to stay aware of their surroundings. "Don't be oblivious. Pay attention to what's going on around you. That's the No. 1 thing," he said. "The second thing is make sure people know where you are at all times. Tell people where you're going, what you're doing, and what time you expect to return."

He cautions against relying on a cell phone during an emergency. The assumption is that, if faced by an attacker or injured by an animal, the veterinarian can quickly and easily access her phone, but that is dependent on good reception and a charged battery to be of use. Seibert recommends veterinarians use dash cameras in their trucks and take advantage of personal alarm devices similar to those used by elderly people. Worn around the neck or on clothing, the device can be activated even during a struggle.

Veterinarians may also benefit from a lone-worker safety device. This technology involves a heavy-duty device that is worn or a cell phone app for employees working remotely that immediately alerts the employer when the employee is in distress or misses a check-in. The types of devices and services vary, with some relying on cellular service while others use satellites to provide real-time tracking.

Those are the scenarios more concerning to me as a black, male veterinarian in the South—driving in rural areas where I know that racism is alive and prevalent.

Dr. Allen Cannedy, practice owner and chief diversity officer at North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine

Dan Smith, director of sales and marketing for Grace Industries, manufacturer of Grace Lone Worker, says the Fredonia, Pennsylvania, company is currently developing an application that will use a satellite connection from a veterinarian's vehicle. "The veterinarian would carry one of our worn devices that transmits back to the vehicle and then transmits over a satellite connection that interfaces with the cloud where the alarm condition is processed, and a notification is sent to a monitoring party," Smith explained.

If Seibert were grading the veterinary profession on personal safety and security, he would be "generous" in giving veterinarians a D. "The overwhelming majority of the profession doesn't see the problem because they haven't experienced it themselves," he said, adding that veterinarians are generally reluctant to publicize when they've been the victim of a crime.

"We think it's a private issue, like we're embarrassed about it, so we don't talk about it, which has got to change," he said.