Invasive tick spreads in U.S., likely to stay

A tick that spreads zoonotic disease in East Asia and Pacific nations is infesting people and animals in at least nine U.S. states.

Asian longhorned ticks, Haemaphysalis longicornis, spread hemorrhagic fever in humans and can feast on animals in the hundreds or thousands. A 2016 scientific article from New Zealand describes infestations that killed cattle and reduced milk production among survivors.

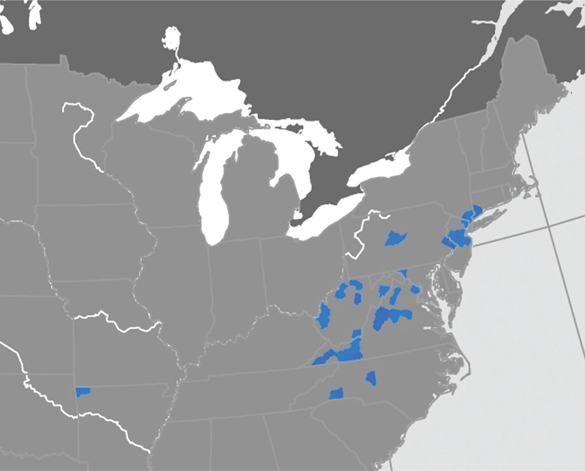

The ticks have been found in Arkansas, Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, Maryland, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. They are native to China, Japan, Korea, and eastern Russia and established in Australia, New Zealand, and several other western Pacific nations.

An article in the Nov. 30 edition of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report states that researchers in Asia found that the ticks carry species of Anaplasma, Babesia, Borrelia, Ehrlichia, and Rickettsia. In China and Japan, the ticks spread the thrombocytopenia syndrome virus, which causes hemorrhagic fever in humans, and Rickettsia japonica, which causes Japanese spotted fever.

The ticks also may spread the Heartland and Powassan viruses, as well as the Theileria protozoa that infest cattle herds in Africa, Asia, and Europe.

"Where this tick exists, it is an important vector of human and animal disease agents," the report states.

Infestation in the U.S. warrants increased surveillance in animals and environments, the report added.

Population and breeding

Veterinary parasitologist Dr. Susan E. Little said the ticks likely are here to stay.

"Once a tick is found on a diverse group of wildlife—different species of wildlife—it's next to impossible to eradicate," she said.

Dr. Little is co-director of the National Center for Veterinary Parasitology and a professor of veterinary pathobiology at Oklahoma State University, where she leads research on zoonotic parasites and vector-borne infections. She also is a co-author of the November MMWR article.

Dr. Little noted that the tick survived winter in New Jersey to emerge in spring 2018, has been found on dogs after travel between states, and has been collected from deer, opossums, raccoons, sheep, foxes, and people. Faculty at the OSU Center for Veterinary Health Sciences have added the ticks to the core curriculum, she said.

The ticks are likely to spread, with limits in regions with cold climates, Dr. Little said.

In an article published online in December in the Journal of Medical Entomology, Rutgers University laboratory director and entomologist Ilia Rochlin, PhD, wrote that the Asian longhorned tick would be best suited to coastal regions in Canada and the U.S., from New Brunswick to North Carolina and southern British Columbia to northern coastal California. It also likely would be suited to central states and provinces from northern Louisiana to southern Ontario and Quebec, with the best of those habitats in the U.S. Midwest.

Health authorities in New Jersey first identified the ticks in the U.S. in August 2017, but retrospective studies indicate they have been in the U.S. at least since 2010, when they were collected from a deer in West Virginia. In a scientific article published early last year in the Journal of Medical Entomology, public health authorities from Hunterdon County, New Jersey, described discovering the infestation in New Jersey. Hundreds of the ticks infested one sheep, which was the lone animal in a paddock.

The investigators found engorged ticks all over the sheep, with the highest concentration of them on the animal's ears and face. Ticks crawled on the investigators' pants soon after they stepped inside the paddock.

The investigators also found only one male tick in their samples, indicating the ticks may have come from a parthenogenetic population in which females can reproduce without males, which are rare in those populations.

Tick control

Tick control products used in the U.S. have been effective against the Asian longhorned tick in other countries, although none are labeled yet for that use in the U.S., Dr. Little said. Veterinarians in Australia, New Zealand, and Japan can control the ticks with isoxazoline-class drugs, which include U.S.-approved products Bravecto, Credelio, Nexgard, and Simparica.

"The products we're already using for dogs and cats will be effective against this tick, so that's reassuring," she said. "And then the pyrethroids should work, and there's a lot of pyrethroid tick control use in large animals."

Dr. Little also called for veterinarians to think about what types of ticks they are finding and how they can identify them. OSU is conducting a tick survey and she said others are conducting tick surveys as well.

CDC officials also announced in November 2018 that about twice as many people in the U.S. had confirmed tickborne disease, compared with a decade ago. About 59,000 people had known tickborne disease infections in 2017, up 10,000 in one year and 27,000 in 10 years.

In 2017, more than 70 percent of those people had Lyme disease. The report also shows rises in anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis, which were reported together, as well as spotted fever rickettsiosis, babesiosis, tularemia, and Powassan virus infection.

CDC authorities don't know why disease increased but listed possible factors including changes in temperature, rainfall, humidity, host populations, tick population densities, and health care provider awareness.

Related JAVMA content:

Options available to protect against longhorned tick (Sept. 15, 2018)

Study offers free identification of ticks from canine, feline patients (Sept. 15, 2018)