Finding lead in pets

Pets may have an underrecognized risk of lead toxicosis.

Dr. Daniel K. Langlois, an assistant professor at the Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine, said toxicosis probably is rare, but testing is uncommon. In addition, lead exposure is associated with nonspecific neurologic and gastrointestinal clinical signs, and lead toxicosis can be mistaken for other diseases.

He said Michigan State's Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory received infrequent requests for blood lead tests before the 2015 identification of a lead contamination crisis in the Flint, Michigan, municipal water supply. With the exception of case reports, he also has seen little published on lead exposure in dogs or cats over the preceding 20 years.

Dr. Langlois ran a series of clinics to test blood lead concentrations in dogs during 2016 in Flint, and he is lead author of a JAVMA scientific report on the results. Their testing showed that the median blood lead concentration for Flint dogs was 4 times the median concentration among dogs in control populations even after the contamination had been identified and most owners had started giving their dogs water from alternative sources.

Federal documents indicate Flint's contamination resulted from a change in the water supply and failure to apply corrosion control. But the JAVMA article notes that other U.S. cities use lead-containing pipes and solder, and lead exposure is a problem beyond Flint.

Dr. Langlois said in an interview he was not suggesting that veterinarians test for lead first when dogs have gastrointestinal disease or consider it first in response to neurologic signs. But he recommends considering lead exposure when no other explanation is available.

In the absence of surveillance for lead exposure in pets, the number or percentage of pets with exposure or toxicosis is unknown. The available data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Environmental Protection Agency provide some indication of how many homes have lead exposure risks. Most of those data are from public health campaigns intended to reduce lead exposure in children.

The CDC estimates about 500,000 children ages 1-5 years have blood lead concentrations exceeding 5 micrograms per deciliter, the concentration at which the CDC recommends public health action. About 3 percent of the 2.4 million children tested in 2015 had concentrations exceeding 5 micrograms per deciliter, and 0.5 percent had concentrations of at least 10 micrograms per deciliter.

A CDC spokeswoman said those figures likely underestimate how many children have lead exposure. Not all children are tested for blood lead concentrations, not all states require reports for lead exposure, and not all states participate in the CDC's surveillance.

Separate EPA information indicates that, when all U.S. children are counted, more than 1 million have been poisoned by lead from old paint alone.

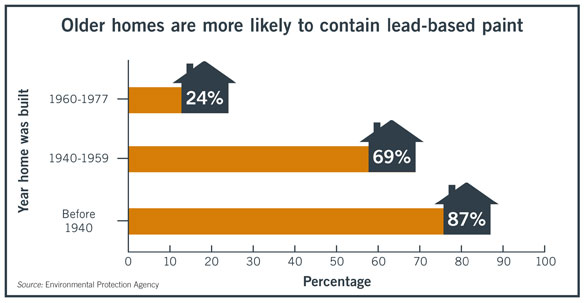

The risks increase with the age of a home.

The EPA warns that homes built before 1986 likely have lead or lead-containing pipes, fixtures, and solder. Until January 2014, new pipes, fittings, and fixtures could be 8 percent lead.

About 24 million U.S. homes have deteriorating lead-based paint, according to the CDC, and paint dust is the most substantial source of lead poisoning in children.

Dr. Langlois' JAVMA article cites among its sources a December 1986 article, "Review of lead poisoning in dogs," which indicates lead toxicosis then was the most common accidental poisoning in domestic animals. It was published in the Veterinary Bulletin of the Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, Weybridge, England. Even then, accurate prevalence data were unavailable.

Detection is rare

John P. Buchweitz, PhD, toxicology section chief at the MSU Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory and a co-author of the Flint article, said lead toxicosis identified in pets before the crisis in Flint tended to be associated with known exposures, such as ingestion of paint chips.

In the four years preceding the Flint water crisis, Dr. Buchweitz said the laboratory conducted blood lead tests on 233 dogs and found 21 had lead exposure, defined by blood lead concentrations of at least 50 parts per billion. Six had clear toxicosis, with concentrations of at least 350 ppb.

Dr. Buchweitz has seen an increase in blood lead test submissions from Flint and neighboring communities since the city's water contamination was identified, but he has seen no change in submissions from areas outside Michigan. He declined to identify the communities.

The 387 tests conducted in 2016, which include the Flint study, found that 11 dogs met that definition for lead exposure, and at least one had toxicosis.

Dr. Robert H. Poppenga, a professor of veterinary clinical toxicology at the University of California-Davis, said veterinarians submit few blood samples for lead testing to the university veterinary diagnostic laboratory, and toxicosis has not seemed to be a common consideration. Two or three dogs had confirmed toxicosis in the past decade, but he did not remember any cats in which toxicosis was confirmed.

The public may think lead use is restricted and not see environmental release as a substantial issue, he said.

Dr. Poppenga is part of a research team that recently found that about 3 percent of backyard chickens submitted for necropsy were positive for lead exposure. The study examined the livers of 1,200 chickens, most from urban areas.

Some passed enough lead into their eggs that a child eating one egg daily would exceed EPA-recommended lead ingestion limits. Yet, most chickens lacked clinical signs of illness, Dr. Poppenga said.

Dr. Tina Wismer, medical director at the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals' Animal Poison Control Center and author of the chapter on lead in the 2013 book "Small Animal Toxicology," said about 300 people have called the ASPCA about lead exposure in pets over the past 10 years. Most called about acute exposures, especially through paint chips from window sills or dust from remodeling.

Poison control hotline operators also have recommended blood lead tests when callers described strange neurologic signs. Lead is one of few causes of intermittent seizures in cats, for example.

But Dr. Wismer also noted that lead toxicosis causes varied clinical signs, including lethargy, behavioral changes, and anemia. Checking a blood lead concentration can help rule out lead poisoning, she said. She also noted that lead deposits can be seen in radiographs.

In "Small Animal Toxicology," Dr. Wismer wrote that dogs and cats can be exposed to lead through automotive batteries, bone meal supplements, ceramic glazes, fishing weights, curtain weights, lead paint, solder, putty, and caulk.

"Gastrointestinal absorption of lead in adult animals varies from 5% to 15% depending on the physical form, whereas young animals absorb lead more readily, with up to 50% being absorbed," the book states.

Inhaled lead is almost fully absorbed, Dr. Wismer wrote.

A 1994 report, "Household pets as monitors of lead exposure in humans," indicates researchers with the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine found that dogs and cats were more likely than their owners to have high blood lead concentrations. The study, conducted for Illinois' Hazardous Waste Research and Information Center, examined effects of lead-contaminated soil on dogs, cats, and children near a shuttered lead smelter.

About 30 percent of pets and 13 percent of people had high blood lead concentrations, according to the report. Dogs and cats increase their risk through chewing, digging, and grooming.

"There is a strong, positive relationship between BLC in animals and their owners, especially pre-school children," the report states. "Because testing an entire population potentially exposed to lead is such a costly and stressful process, it is our suggestion to test dogs and cats instead."

Dr. Buchweitz said animals, especially pets, can be sentinels for health risks to humans. Dr. Wismer said that, in areas where animals have lead poisoning, people should be tested.

Prevention needed

The American Academy of Pediatrics published in 2016 a policy statement indicating lead toxicosis remains a public health priority in the U.S. Blood lead concentrations in U.S. children have declined over the past four decades, a period during which leaded gasoline was phased out, the allowable lead content of paint was decreased to 90 parts per million, regulations under the EPA Lead and Copper Rule forced reductions of lead content in tap water, and lead solder was banned from use in canned foods.

"It is difficult to accurately apportion the decline in blood lead concentrations to specific sources, but the combined effect of these regulations clearly led to the dramatic reductions in children's blood lead concentration," the article states. "The key to preventing lead toxicity in children is to reduce or eliminate persistent sources of lead exposure in their environment."

Jennifer Lowry, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Environmental Health and section chief for toxicology and environmental health at Children's Mercy Kansas City, said Flint's water contamination crisis showed the public that lead contamination remains in our environment. It also temporarily turned attention toward water and away from more common sources of exposure, such as paint chips.

In children, lead poisoning mimics other diseases or can be asymptomatic. Neurologic effects can be subtle. Delayed speech is discovered at 2-3 years of age, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is discovered at school age, she said.

Where lead-contaminated dust can affect children, for example, she expects it also could affect animals in the home. Testing pets for exposure is worth considering, she said.

"In order to fix this problem, there needs be an effort for primary prevention," she said. "Because once an animal or a child has an elevated lead level, it's too late, right? Now we have to play catch-up."

She said that, in human medicine, physicians could help prevent poisoning by asking new parents about the age of their home, the state of repair, their occupations, and their hobbies. But those tasks are not performed in pediatric medicine.

"We don't have the funding, really, to do primary prevention the way it needs to be done," she said. "But that's the way to solve it."