Studies confirm poor well-being in veterinary professionals, students

U.S. veterinarians got their first glimpse of the extent to which mental health and well-being issues occur among them in the study “Risk factors for suicide, attitudes toward mental illness, and practice-related stressors among US veterinarians” (J Am Vet Med Assoc 2015;247:945–955).

Since then, a handful of surveys have looked deeper at the wellness of not only veterinarians but also other veterinary professionals and veterinary students. In addition, a group of researchers, inspired by the JAVMA risk factors study, have gotten together to look at how occupational health factors into mental health outcomes. They are also hoping to involve the veterinary community in shaping their research focus.

Work-related stress a concern

Randall J. Nett, MD, principal co-investigator of the risk factors study, attended the AVMA veterinary profession wellness roundtable, held March 14-15 in Schaumburg, Illinois. He said one key finding from the study was that veterinarians who likely had less social support were more likely to suffer from serious psychological distress. Characteristics associated with poorer psychological health included not being married or in a committed relationship, being separated or divorced, not having children, and not being a member of a veterinary medical association.

In addition, those experiencing serious psychological distress were less likely to agree that mental health treatment helps people lead normal lives and that people are caring toward persons with mental illness. Eighty-three percent of survey respondents somewhat or strongly agreed that mental health treatment was accessible. In contrast, the 17 percent of respondents who were unsure or who disagreed or strongly disagreed about accessibility of mental health treatment were more likely to have current serious psychological distress, less likely to currently be receiving mental health treatment, and more likely to have experienced prior suicidal ideation.

“Veterinarians in general, but especially those with serious psychological distress, perceive a certain degree of stigma toward those who have mental illness,” he said.

Dr. Nett, a medical officer for the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said the most commonly reported stressful factor associated with veterinary medicine was the demands of practice. This was echoed in another survey, being conducted by Tracy K. Witte, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at Auburn University. She co-authored the risk factor study and attended the roundtable.

Dr. Witte surveyed veterinarians along with veterinary technicians, assistants, and receptionists in Alabama and Tennessee starting this past January. So far, about 280 people have responded to the needs assessment, which will be used to inform planning for wellness interventions in these states.

The biggest concern that respondents indicated was work-related stress. The results also show that veterinarians have rates of job satisfaction, substance abuse, exposure to work-related trauma, and distress and other mental health symptoms similar to rates among other veterinary professionals.

As was the case for the risk factor study conducted by Dr. Nett, respondents in this survey had higher rates of lifetime depression (25 percent) and suicide ideation (18 percent) and similar rates of past suicide attempts, compared with rates for the general population. Plus, 26 percent of respondents scored beyond a cutoff indicating problematic drug or alcohol use disorders.

“Fortunately, most veterinary professionals will not experience suicidal behavior, but what stood out was work-related stress, with work overload being the main stressor of the profession,” Dr. Witte said.

When asked where future efforts should be focused in their state, most respondents listed education about risk factors for mental health and substance abuse as well as stress management, while increasing the availability of psychiatric or drug abuse treatment ranked low. It’s possible these needs are already being met, Dr. Witte said, and that’s why they ranked low.

“I think it’s important that we are focusing on people who are suffering and directing them to resources. But this is just one part of wellness, and we need to teach stress management on top of that,” she added.

Canada, too, is looking at the mental health and well-being of its practitioners along with others in the animal health industry.

Four studies are underway at the University of Guelph’s Ontario Veterinary College that involve farmers, veterinarians, and veterinary students.

Preliminary findings from a study of more than 500 Canadian veterinarians conducted this past summer indicated that roughly a third of the participants have anxiety, with another third considered borderline. Almost one in 10 were classified as having depression; about three in 20 were in the borderline category. Forty-seven percent of respondents scored high on emotional exhaustion, one of three components of burnout. Three-quarters of respondents fell below the mean on resilience scoring for the general U.S. population.

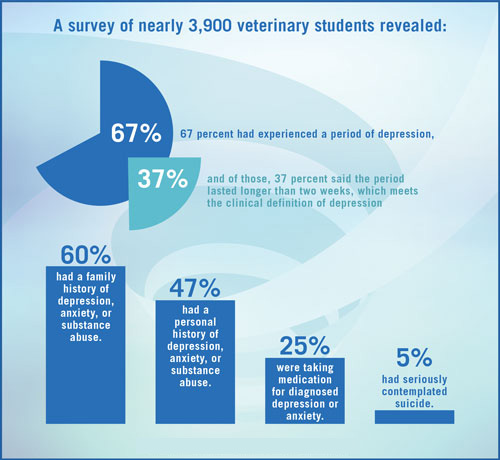

To address these issues among veterinary students, the Student AVMA created a Mental Health & Wellness Task Force in 2015. The task force sent a survey to SAVMA’s nearly 14,000 members to gauge their mental health. Of the 3,888 who responded:

- 67 percent had experienced a period of depression, and of those, 37 percent said the period lasted longer than two weeks, which meets the clinical definition of depression.

- 60 percent had a family history of depression, anxiety, or substance abuse. 47 percent had a personal history of depression, anxiety, or substance abuse.

- 25 percent were taking medication for diagnosed depression or anxiety.

- 5 percent had seriously contemplated suicide.

Michael McEntire, co-chair of the task force and a third-year student at the Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, said the rates of depression, self-harm, and suicidal ideation all went up in students in their clinical year. In addition, results showed rates of suicidal ideation went up 0.5 percentage points for every $50,000 a student was in debt, which would suggest that debt is more of a compounding factor than a direct cause, he said. The survey also found a strong correlation between students feeling that professors care about them and how comfortable students felt seeking help. McEntire said, from a student perspective, having faculty members open up about their own struggles would set a good example.

Veterinary colleges’ specific aggregate results have been sent to administrators at each institution as well as to the VMAs that have veterinary schools in their states.

Future research efforts

Given the prevalence of poor mental health and well-being in the profession, some researchers are starting to look at the issue from an occupational health perspective.

Following publication of the JAVMA study on risk factors, a few investigators got in touch with the authors, including Dr. Meghan Davis, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health; Peter Rabinowitz, MD, associate professor in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences at the University of Washington School of Health and director of the Center for One Health Research; and Dr. Heather Fowler, a doctoral student at UW and associate director of animal health at COHR.

A team of about 20 people has gotten together to plan and implement research that would incorporate mental health into occupational health outcomes. They also seek to explore intramural efforts to help promote these areas of interest. A few, including Drs. Davis, Rabinowitz, Fowler, and Nett, work at Education and Research Centers funded by the CDC’s National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. These centers exist to train future occupational health professionals through interdisciplinary programs.

“Overall, we propose greater cross talk between human health care professionals and veterinary health care workers to share ideas about occupational health and wellness, since there are many overlapping issues, and the two groups have much to learn from each other,” Dr. Rabinowitz said.

Drs. Rabinowitz and Fowler are already working on research in this area, including reducing the risk of animal-related injuries through a one-health, train-the-trainer approach that includes factors related to the work environment, such as the safety culture, and to individual behavior and animal behavior.

They’re also considering looking at the psychological wellness of veterinary and other animal workers, including factors such as professional burnout, compassion fatigue, and stress from animal euthanasia. There’s interest, too, in establishing and following a cohort of veterinary workers to assess and help reduce occupational health risks and enhance wellness.

Dr. Rabinowitz’s department has a NIOSH-funded training program in Occupational Health at the Human-Animal Interface, the first NIOSH-funded program of this kind. Through this program, the department is focusing on the occupational health of veterinary and other animal workers such as farm, zoo, and laboratory animal workers.

Dr. Fowler is working toward her doctorate in occupational and environmental hygiene, focusing on the occupational health of veterinary workers. Another veterinarian, Dr. Julianne Meisner, is getting her master’s degree in occupational health of animal workers as an OHHAI scholar. Dr. Rabinowitz says the hope in the future is to train more veterinarians in occupational health.

Meanwhile, Dr. Davis, a 2000 veterinary graduate of the University of California-Davis, intends to develop one or more cohorts of veterinarians in the next three years to evaluate outcomes, one being mental health and suicide. A potential focus area is pathways to intervention for veterinarians in need of help, which could be at a policy level or on an individual level.

“What are the barriers for veterinarians specifically? We sometimes have a challenging, time-consuming, and demanding occupation that is absolutely rewarding but comes with barriers to seeking help where others in another profession might have better access to assistance,” she said.

There will not be one grand study, Dr. Davis said. Instead, this group of researchers is looking to break down the topic of wellness in the veterinary profession and piece together a more complete picture.

Most important, Dr. Davis said the group is equally interested in hearing from veterinarians and veterinary technicians. The researchers are looking to form partnerships at the concept stage of research investigations and include stakeholders who want to be involved in designing studies, writing grants, performing research, and communicating findings back to the profession and scientific community.

“It’s a critical need and one we can’t afford to ignore,” Dr. Davis said. “With mental health, I hope we can benefit the profession as much as veterinarians benefit science. That’s the goal: to actually make a difference in people’s lives.”

Get Involved

Individuals interested in getting involved in research on the mental health of veterinary and allied health care professionals should contact Dr. Meghan Davis at mdavis65 jhu [dot] edu (mdavis65[at]jhu[dot]edu); Peter Rabinowitz, MD, at petterr7

jhu [dot] edu (mdavis65[at]jhu[dot]edu); Peter Rabinowitz, MD, at petterr7 u [dot] washington [dot] edu (petterr7[at]u[dot]washington[dot]edu); or Dr. Heather Fowler at hfowler

u [dot] washington [dot] edu (petterr7[at]u[dot]washington[dot]edu); or Dr. Heather Fowler at hfowler uw [dot] edu (hfowler[at]uw[dot]edu).

uw [dot] edu (hfowler[at]uw[dot]edu).

Related JAVMA content:

Student AVMA ready to reinvent (May 15, 2015)

Study: 1 in 6 veterinarians have considered suicide (April 1, 2015)

RCVS puts money toward mental health resources (April 1, 2015)

Moral stress the top trigger in veterinarians’ compassion fatigue (Jan. 1, 2015)

The toll it takes to earn a veterinary degree (Dec. 15, 2014)

Finding calm amid the chaos (Nov. 15, 2013)