Veterinary antiques: A lesson in history, the profession, advertising, and collecting

|

The graphics on the tin front dazzled Dr. Smith. His wife turned to him and said, "You have to own that!" The rest, as it's said, is history.

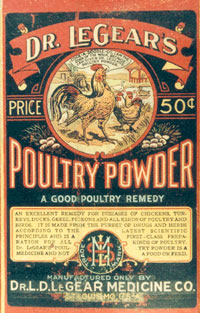

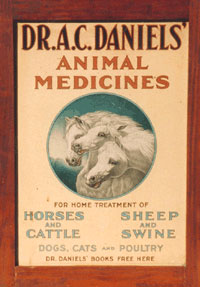

He's hooked "At the time, I had no idea if the purchase was good or bad, or we had paid an absolutely astronomical amount of money," said Dr. Smith, who would some 10 years later start the bimonthly newsletter Dr. Michael Smith's Celebrated Veterinary Collectibles Roundtable. The purchase was a good investment. The cabinet he paid $300 for in 1981 is worth $2,500 today. The search for more items was on, but without the convenience of Internet search engines or auctions, he had to do some good, old-fashioned footwork. "I talked to several veterinary libraries, antique dealers, and historical societies," he said. "From my cabinet, I knew [the] Dr. Daniels' [company] was from Boston, so I contacted the particular area. If I found a bottle of old medicine with a readable label, I would contact the town where it was manufactured." Slowly, after a few years of searching, Dr. Smith found more pieces and met a few other veterinarians who had the same interests. Patent medicine  In reality, these formulas were never patented at all, and for the most part, there was little medicinal benefit to them. Montague's Poultry Powder from Rocky Mount, Va., contained oyster shells and charcoal. Dr. Clayton's Tonic and Stimulant for Dogs, out of Chicago contained arsenic, iron, and sulfur. Many colic treatments for horses contained as much as 78 percent alcohol, in addition to opium and morphine. "A lot of the patent medicine people lived off the fear of the farmer about his animals," Dr. Smith said. Horses, chickens, and livestock were the lifeblood of the farmer and his family, and when their animals' health seemed off, the farmer had to rely on the products at the general store. And, very few "doctors," as advertised on the product labels, had traditional veterinary medical training. In collecting, the items before 1906 are the most desirable, and the hardest to find. After the Pure Food and Drug Act, companies could not make a claim on the product that could not be backed up. The act eliminated the word "cure" from advertising for any product, and the word "remedy" started showing up more. "You can often date an item by looking at how the name of the product changed through the years," Dr. Smith said. "It would go from Dr. Glover's Mange Cure for Dogs, to Dr. Glover's Remedy for Dogs, to Dr. Glover's Mange Medicine for Dogs." Hoaxes as history?  Dr. Smith and Dr. Ken Opengart, collector and director of veterinary services for ConAgra Poultry Company of Athens, Ga., were discouraged in their beginning efforts to publicly recognize these antiques as important pieces of the puzzle of veterinary medical history. It was better, they were told by some veterinary medical organizations, that this part of the past should be forgotten. This kind of collecting was outside the bounds of traditional veterinary medicine. "I think just the opposite," Dr. Opengart said. "I do think these items are a part of the history of our profession. Besides just the beauty of some of these items, it's a look at just how far we've come." The American Veterinary Medical History Society does recognize items such as veterinary display cabinets, patent medicines, doctor reminder cards, stamps, equipment, and books as meaningful historical markers of the profession. "These objects are crucial to our understanding of the history of veterinary medicine," said Dr. Susan Jones, a veterinarian who also has a doctorate in history, and is the current president of the American Veterinary Medical History Society. "In large part," she says, "veterinary history is comprised of the collective actions of all these people ... through old journals and advertisements, we can understand the world in which they lived and the concerns they had. Thus, material culture represents important historical evidence." Collectors as curators At the University of Missouri-Columbia College of Veterinary Medicine, librarian Trenton Boyd's passion for deltiology—postcard collecting—may put UMC's library on the veterinary history map as well. Boyd has a collection of 2,600 postcards on veterinary medicine, some of which are worth up to $200 apiece. In 1994, he addressed the 27th International Symposium on the History of Veterinary Medicine, sponsored by the World Association for the History of Veterinary Medicine, on the importance of using postcards to document history. His interest was sparked while collecting postcards on Missouri, when he stumbled across a postcard of a clinic in Springfield, Mo. He categorizes his collection according to veterinary colleges, museums, associations, veterinarians in the military, clinic reminder cards, and veterinarians in action, to name a few. Some professors at the college have made his postcards into slides to accompany lectures. "A friend of mine at the Missouri Historical Society told me that one of the best ways to document history is through photographs and these images," Boyd said. "You just don't know how your collection can be used, and in what way." The demand  "Now I think, because of the Internet and the Antiques Road Show [on PBS], more and more people have decided that antiques are a good investment," she said. "When I put the items on Zydaco's Web site, I have people contacting me before they see the prices. The cabinets are the big sellers." Dr. Smith agrees that, in the advent of such Internet auction sites such as eBay, the veterinary collecting community has seen more new faces, and more competition. "I know guys who have been collecting for over 30 years, and there are new collectors: new kids who are getting out of school and who are fascinated with the history [of veterinary medicine] who have started collecting," Dr. Smith said. The appeal For most, it is those graphics coupled with the times that is the charm of each piece. Dr. Opengart owns boxes of medicine for Federal and Union Poultry Powder. An Imperial Egg Food trade card depicts America's victory over Great Britain in the 1885 America's Cup Race. But veterinarians aren't the only ones interested in such collectibles, as the old country store motif is popular in antiquing. "These are people who want to turn their basement or rec room into an old country store," Dr. Smith said. There are dog trainers and pet store owners who are interested as well. To be specific, of the 200 who subscribe to his newsletter, he says about 85 percent are veterinarians. "And I believe I know everyone in America that does this kind of collecting," he said. It takes a certain passion, instinct, and to a degree, peculiarity, to collect just about anything. Friedman sums it up nicely as simply, "It's a matter of personal taste." For more information about acquiring veterinary collectibles, contact Dr. Mike Smith at http://petvet.home.mindspring.com/VCR/ or Karen Friedman at http://home.earthlink.net/~zydaco/. | ||