Confiscated Asian turtles treated in marathon rescue effort

|

| |

|

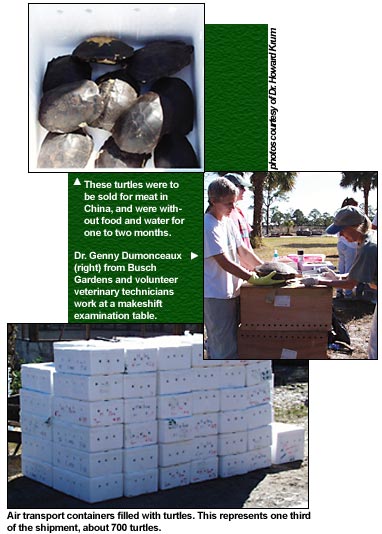

The shipment, with an estimated black market value of $3.2 million, was apprehended en route from Borneo and Sumatra to the meat markets in China. This record seizure sparked the largest coordinated international turtle rescue in history. The burgeoning Chinese appetite for turtle meat is literally devouring wild stocks of Asian turtles. Traditionally, freshwater turtles and land tortoises are used for food and ancient medicinal remedies, including aphrodisiacs and treatments for impotence. But recent surges in economic prosperity have led to the development of an affluent Chinese middle-class population and, as incomes have grown, so has the demand for turtles. "There's nothing wrong with a culture that enjoys eating turtles," said Memphis Zoo veterinarian and turtle crisis respondent, Dr. Chris Tabaka. "But because of the scale and all the new income, they started eating all the turtles in China." Dr. Barbara Bonner, owner of the New England Turtle Hospital, adds, "This is the biggest crisis to hit reptiles since the dinosaurs went extinct." Because intense poaching pressures rule out release of these animals to the wild, members of the U.S.-based Turtle Survival Alliance arranged for airlines to donate the shipment of almost half of the smuggled turtles to a way station in southern Florida. Some of the remainder are being held temporarily at the Kadorie Botanical Preserve in Hong Kong, while others have been distributed to zoos and aquaria throughout Europe. On Jan. 13, volunteers descended on the Appalatah Flats Turtle Preserve, near Miami, when the last of four massive shipments arrived in the United States. The group triaged and treated approximately 2,100 turtles during a marathon, three-day, MASH-style medical session. Drs. Paul Calle and Bonnie Raphael, senior veterinarians for the Wildlife Conservation Society at the Bronx Zoo, led a team of veterinarians conducting the initial triage. Animals were unpacked from foam shipping boxes and examined in order of species status—the most critically endangered first. Turtles were then sorted into one of five triage groups and treated accordingly. Those with a very good prognosis received a "T1" designation while "T5s" were directed to the on-site necropsy team staffed by pathologists from Disney's Animal Kingdom. After initial triage, each animal was assigned a personal "runner" who transported the animal and its medical record through a maze of examination, treatment, and tissue sampling stations. To make sure that each turtle was not lost in the sea of chelonian patients, a unique pattern of notches was quickly carved in marginal scutes for permanent identification. Turtles from the most critically endangered species also received passive-integrated transponder implants. All aquatic species were then examined with metal detectors, because they are commonly poached via hook-and-line. Those positive for metal foreign bodies—presumed fishhooks—were diverted from the main patient flow and shuttled to a local small animal practice for a radiographic workup. Dr. Ross Prezant, owner of the All Creatures Animal Hospital of Stuart, Fla., donated the use of X-ray facilities, staff time, and all supplies necessary to work up over 40 individuals. "Radiographically, we found that 90 percent of the animals tested positive via metal detectors did have fishhooks," Dr. Prezant said. Volunteers set up nine makeshift examination tables on empty turtle shipping containers in the shade of a nearby palm tree grove, with at least one veterinarian and a scribe recording physical examination findings and treatments administered. A circulating crew of veterinary technicians replenished stocks of IV fluids, injectable antimicrobials, and parasiticides every few minutes. Closer examination revealed that many animals were in grave medical condition, as most turtles were assigned as "T3s" and "T4s," suffering from a host of problems, including moderate to severe dehydration, shell and limb fractures, lethargy, and cachexia. These findings, though disconcerting, were expected, since originally, three large shipping containers held over four tons of turtles. The animals, stacked one on top of another, were held captive in this condition for one to two months without access to food or water. Following medical treatment and reassessment of triage status, runners ferried turtles to the blood collection station, where samples were collected for future conservation research initiatives, including DNA analysis for comparison with remaining wild stocks. Since the TSA researchers do not know exactly where the turtles were poached, these analyses will give clues to their original habitat and, hopefully, guide future reintroduction efforts. Following DNA collection, turtles were prepared for further treatment on-site or for distribution to temporary homes. In spite of the overwhelming number of patients, all 2,100 animals were evaluated in the first day of the three-day session. "I was impressed with how smoothly things went," said Dr. Greg Lewbart, North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine. Dr. Lewbart led a delegation of the NCSU Turtle Rescue Team. He brought three veterinarians, five veterinary students, and one technician to the Florida mission. "I knew when I saw all the e-mails flying around that we should go. [It was] an opportunity to use our skills and knowledge for animals that really need us, and the students get to see wildlife veterinary medicine in action," Dr. Lewbart said. At press time, NCSU was one of more than 65 locations in the United States providing husbandry and medical care for the turtles. The aftercare required for most of these animals is intense. Just one of Dr. Lewbart's 45 patients, a persistently anorexic, 27 kg Malaysian giant turtle (Orlitia borneensis), has undergone a battery of diagnostic tests, including radiography, ultrasonography, endoscopy, and even 3-D computerized axial tomography, all in an attempt to accurately locate the offending fishhook for removal. "It's like a busy turtle clinic, with the students carrying the bulk of the workload," Dr. Lewbart says. Some students, such as Shane Boyland, are volunteering 25 to 30 hours a week while providing care for these endangered animals. Boyland said, "It's a great experience. The other day, I got to put in my first glossopharyngeal feeding tube. You get to make a real contribution, even as a first-year [student]." Until now, seized Asian turtles were destroyed because there was no place for them to go. "Before the creation of the Turtle Survival Alliance, confiscated turtles were disposed of in an effort to curb illegal harvesting," says Rick Hudson, TSA co-chair at the Fort Worth Zoo."The TSA provides an ideal option, which channels these turtles into captive programs where they can be rehabilitated and managed long term. It's a win-win situation for all involved, especially the turtles." One of the main goals of the TSA is the establishment of assurance colonies. They are essentially biologic time capsules that will allow species representatives to weather the poaching storm. The plan is to ultimately reintroduce progeny of these animals back into protected native habitats. "We're not just building collections of turtles," said Dr. Kurt Bulhmann, TSA co-chair. "We want to get them back into the wild. Our goal is to have some of these countries establish national parks where the turtles can live safely, but at the rate they're dying, there's not time for that now. We need to establish some colonies here [in the United States] to make sure they don't go the way of the American bison." For more information, or to make a donation for the veterinary care of these animals, contact Dr. Barbara Bonner of the New England Turtle Hospital at (508) 529-6811; e-mail, turtlehosp | |

More than a hundred volunteers, including veterinarians, technicians, and veterinary students from across the United States, responded en masse to an Asian turtle crisis in December, as Hong Kong conservation authorities intercepted and confiscated a massive shipment of approximately 7,500 endangered and threatened Asian freshwater turtles and tortoises. Their efforts are part of an international program to establish animal repositories—living gene banks—for critically endangered turtles.

More than a hundred volunteers, including veterinarians, technicians, and veterinary students from across the United States, responded en masse to an Asian turtle crisis in December, as Hong Kong conservation authorities intercepted and confiscated a massive shipment of approximately 7,500 endangered and threatened Asian freshwater turtles and tortoises. Their efforts are part of an international program to establish animal repositories—living gene banks—for critically endangered turtles.