Afghan veterinary association finds its way

For decades, Afghanistan has been roiled by conflict. As a front in the war on terror, where combat operations against al-Qaida and the Taliban are ongoing, it's hard not to imagine Afghanistan as rife with violence and lawlessness. Yet a recent gathering of Afghan animal health workers illustrated that reality in Afghanistan is markedly different from the headlines.

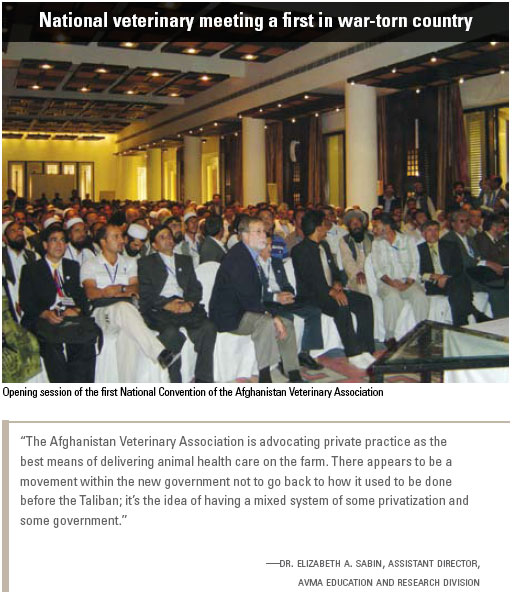

Dr. Elizabeth A. Sabin, an assistant director of the AVMA Education and Research Division, was the AVMA's representative at the first National Convention of the Afghanistan Veterinary Association, held Sept. 4-5 in Kabul. Funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Agency for International Development made the meeting possible. The meeting, themed "Food security through animal health," was especially noteworthy as it was the first meeting of a professional association in Afghanistan, according to Dr. Sabin, who gave a brief presentation about the history of the AVMA and the importance of meetings and conventions.

"I talked about how the AVMA started as a small group over a hundred years ago and how it's grown to be a national organization representing the veterinary profession. I told them it's not all that different from how the AVA was started," Dr. Sabin said.

Afghanistan is an agrarian society. For years, the nation's animal health needs, primarily those of livestock, had been mostly funded by the government. Over the past two decades, however, government support has become increasingly limited. The AVA was formed in 1996 as a buying and distribution cooperative to pick up where the government had left off. Rather than relying on payment from the government, members of the association adopted a fee-for-service model, marking the beginnings of private veterinary practice in the country.

The AVMA's dealings with the AVA started during the International Veterinary Conference in Kuwait City in 2004. Since then, the AVMA has worked with the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges on a task force assessing the veterinary infrastructure in Afghanistan and Iraq. The AVMA also assisted the AVA in hiring a consultant, Bill Bell, executive director of the Maine VMA, to guide the association and its board of directors.

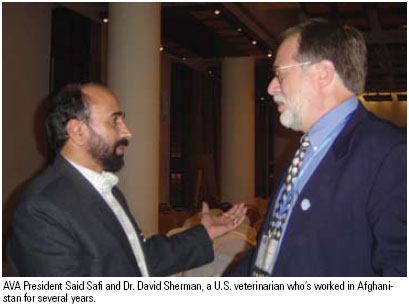

Afghanistan Veterinary Association President Said Safi attended the AVMA Annual Convention in 2005 and 2007 and invited the AVMA to the historic Afghan meeting. "Having a distinguished guest from the AVMA helps (AVA members') understanding, develops the confidence of friendship, and may lead to a very good bilateral professional relationship in the future in many ways," Dr. Safi explained to JAVMA News via e-mail.

Today, the purpose of the AVA is to enable Afghanistan's veterinary profession to be organized and defend and promote the rights of its members in the practice of veterinary medicine, Dr. Safi stated. "We, like any other professional organization, follow our articles and bylaws in trying to achieve our goals," he said.

More than 500 AVA members attended the national conference, many of them traveling to the capital from distant provinces. Government officials and deans and faculty members of the nation's two veterinary schools were also on hand. Half the AVA members in attendance were veterinarians, with the remainder comprising veterinary technicians and paraveterinarians.

Paraveterinarians are high school graduates who have completed a six-month training program in basic animal health care. The AVA, with help from nongovernmental organizations such as the Dutch Committee for Afghanistan, is largely responsible for training paraveterinarians, who are vital resources in remote parts of the country where veterinarians are in short supply. "Paraveterinarians aren't veterinary technicians. They really are a unique thing," Dr. Sabin explained.

During the two-day meeting, continuing education lectures and discussions covered a range of topics, such as artificial insemination, food safety, recognition and sample collection for infectious diseases, and treatment of common diseases of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, camels, poultry, dogs, and cats. Presentations were given in Dari, with Dari translations provided for the few English-speaking presenters. Lecture halls were standing room only, Dr. Sabin said, and discussions were often spirited.

"There was a lot of interchange of ideas, and that was really neat to see—a lot of dedicated veterinarians and paraveterinarians who enjoyed coming together to share their ideas," Dr. Sabin said. "You could see they were interested in sharing what they were doing and learning from one another."

One of the challenges facing the AVA is its relationship with paraveterinarians. According to Dr. Safi, more than half of the 875 AVA members are paraveterinarians. Dr. Sabin heard from some veterinary students concerned that the AVA is more focused on promoting clinical education and training of paraveterinarians than on veterinary students enrolled in ill-equipped and underfunded veterinary schools.

Another issue is defining the government's role in animal health care. The AVA wants to continue the fee-for-service practice, and for the government to oversee national disease surveillance and control programs, to allow re-entry of Afghanistan's livestock sector into world markets. In addition to nutritional deficiencies and bacterial diseases, illnesses such as "peste des petits ruminants" are endemic, Dr. Sabin noted.

"The AVA is advocating private practice as the best means of delivering animal health care on the farm. There appears to be a movement within the new government not to go back to how it used to be done before the Taliban; it's the idea of having a mixed system of some privatization and some government," Dr. Sabin said.

Veterinarians in the United States need to understand that while there are challenges to working in Afghanistan, it isn't necessarily unsafe, according to Dr. Sabin. Although there are unsafe areas, Kabul is a thriving city undergoing extensive rebuilding. The streets are crowded with people going about their lives, traveling via car as well as by horse- and donkey-drawn carts. Security is evident around government buildings and places where large groups of people gather, but it doesn't hinder daily life.

As one of only a handful of women attendees at the male-dominated meeting, Dr. Sabin said she never felt looked down on. In fact, the Afghan veterinarians were pleased by the presence of foreign guests. Dr. Sabin described the Afghan people as exceptionally courteous and resilient. She recounted how she attended a reception at AVA headquarters and learned that many of the Afghans at the table had lost more than one family member or friend to the decades of war.

"And yet they're still there, and they still have hope for the profession and hope for the future of Afghanistan," Dr. Sabin said. "These people still have great hope in the future, and I don't understand how they can, considering everything they've had to go through, but they do."